The Glory Days of the Hellraiser: Terence Stamp

Ed Cripps concludes this month's three-part series on the last generation of Great British actors who made their names as hell-raisers of the highest order.

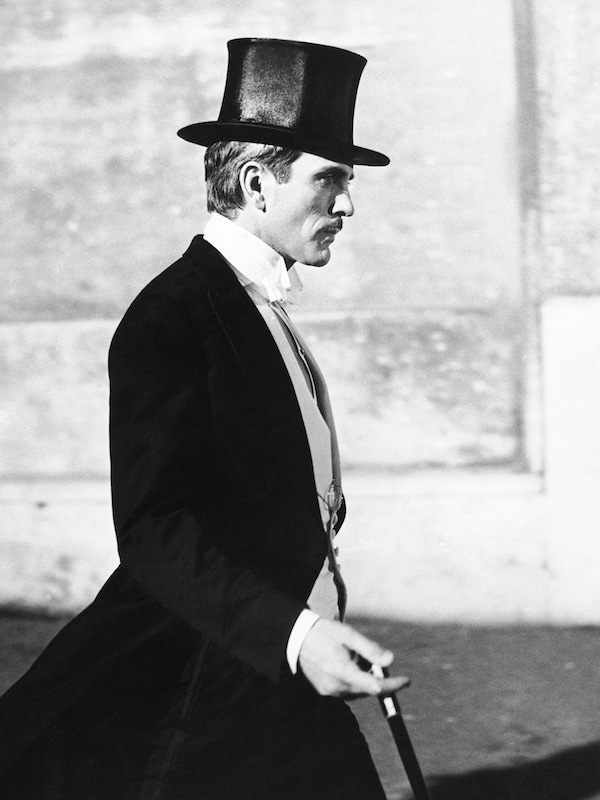

In his heyday, Terence Stamp was an East End Odysseus amongst the lotus-eaters, an unfathomably handsome god with moon-trenched eyes, a star of shatter splayed. The second half of the sixties became the summer of Stamp’s essence, a period he defined so deeply it became difficult to transcend. Now 78, he has slid through decades in cinema on wit, Cockney candour and a street-market awareness of his own iconography.

A tugboat stoker’s eldest son brought up in Bow and Plaistow, he idolised Gary Cooper ever since his mother took him to see Beau Geste at the age of three. After early jobs in advertising and as a golf caddy, a scholarship to drama school led to parts in rep theatre, including The Long and the Short and the Tall alongside a young Michael Caine. His breakthrough in Peter Ustinov’s Billy Budd (1962), for which he won a Golden Globe and received his first Oscar nomination, flowed into rivers of high-literary romance and the European avant-garde that Stamp gauzed with a Wicker Man strangeness: he chilled and won Best Actor at Cannes for William Wyler's The Collector (1965), an adaptation of a novel by John “The Magus” Fowles (a novelist whose limpid English otherness Stamp resembles). His sword-swishing vitality overpowered Julie Christie in John Schlesinger’s Far From The Madding Crowd (1967), and he seduced an entire family as a sort of sex-messiah in Pasolini’s Theorem (1968).

During this Midas age when even his brother Chris managed The Who and Jimi Hendrix, Terence shared a flat with Michael Caine, eight years his senior and whom Stamp called his master. He told The Guardian: “Caine gave me all my early values, like making sure you were doing good stuff, waiting for the right things – then as soon as he got away he did exactly the opposite.” When Stamp was approached to replace Sean Connery as Bond, he “put the frighteners” on the producer with his mordant vision for the role. He also turned down Alfie, a part crafty Michael snapped up. One can only imagine the parties, but Stamp struggled to keep up with elders Caine, O’Toole and Harris: “I was anyone’s after a couple of Scotches. The same with grass: I’d be stoned instantly.”

“I was anyone’s after a couple of Scotches. The same with grass: I’d be stoned instantly.”He wasn’t just anyone’s. According to The Independent he and Caine shared a room with twin beds, so when either took a girl home — “more often him” — Caine would dump his mattress and sheets in the living room behind the sofa to signal that each should withdraw to his separate territory. For all Stamp’s modesty, he dated three of the most beautiful women of the twentieth century. His relationship with co-star Julie Christie was immortalised in The Kinks’ ‘Waterloo Sunset’ (“Terry and Julie cross over the river…”) With supermodel Jean Shrimpton, who left David Bailey for Stamp, he became one of the most photographed couples in London: wistfully he has said in interviews she was the love of his life, but he hasn’t seen her since. He also went on a blind date with Brigitte Bardot in a pair of trousers he’d nicked from the Far From The Madding Crowd wardrobe. He told the Evening Standard:“They’re not normal strides, but I felt comfortable in them. It’s the first time I realised that if you feel good, you look good.” Sadly they didn’t have a shared language and self-confessed “cannibal” Bardot was startled at Stamp’s vegetarianism. Astonishingly for England’s hippest actor, work dried up in the seventies. Stamp claims that producers now wanted “a young Terence Stamp” (he was only 32) and overlooked the man himself, which he found “deeply humiliating”. Introduced to the mystic Krishnamurti by Federico Fellini, he dropped out of cinema-society for seven years to discover himself in India. Eventually, a telegram addressed to “Clarence Stamp” offered him the role of General Zod in Superman and he was coaxed back. After a patrician scene-steal in Wall Street, the old progressive charisma resurfaced as the transgender Bernadette Bassinger in Priscilla, Queen of the Desert (1994), for which he was BAFTA-nominated. He now leads a more minimalist existence, having left London twenty years ago (“English is a foreign language in London”, he controversially posited last year). In 2002, the 64-year-old Stamp got married for the first time to 29-year-old pharmacology student Elizabeth O’Rourke: they divorced six months later. Like Harris and O’Toole, Stamp has the soul of a writer (his publications include three volumes of autobiography Stamp Album, a novel The Night, the acting guide Rare Stamps and a cookbook). He’s probably the oddest of the three hellraisers, the George Harrison: a Cockney patriot who dabbled in Indian philosophy he learnt from an Italian, a hostage to the crucible caresses of his prime, but clearly still in-demand (when he fell off a horse on the shoot of last year’s Bitter Harvest, he joked the headline would be “Distinguished actor killed by horse’s arse”). Thomas Hardy wrote in Far From The Madding Crowd that “we colour and mould according to the wants within us whatever our eyes bring in.” Since the sixties, directors, audiences and lovers have filled Stamp’s blank beauty with their own desires: he remains a magus, an ego-raked echo chamber of undervoices and a timeless time capsule.