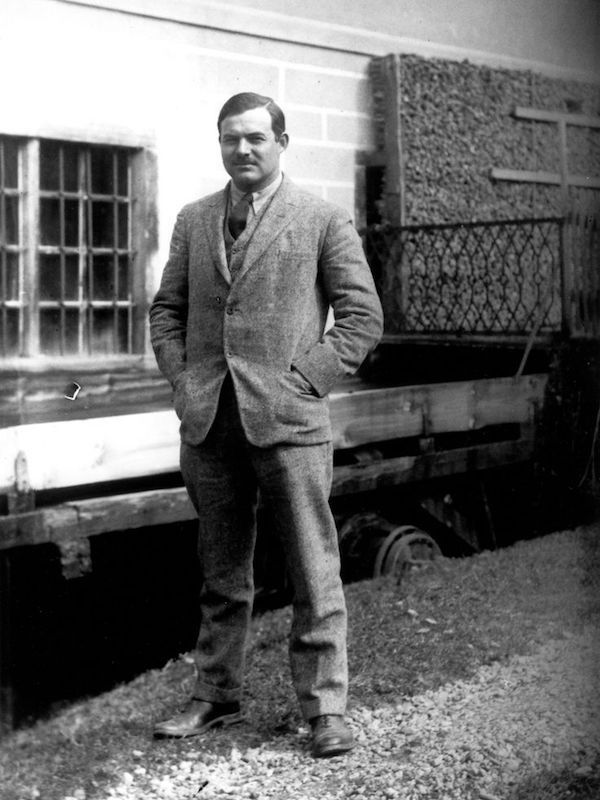

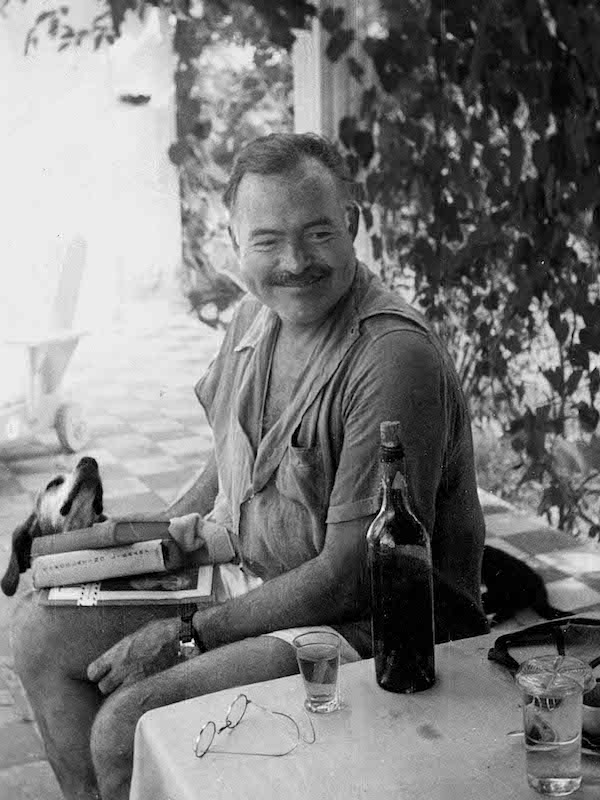

Hemingway’s School of Hard Drinks

"Drinking wine was not a snobbism nor a sign of sophistication nor a cult; it was as natural as eating and to me as necessary..." The Rake examines how Hemingway's reputation as a bottomless receptacle for all things alcoholic survives him even now.

I first encountered the Hemingway Drinking Game during an undergraduate tutorial in one of the lesser ventilated study rooms of the English Department. A fellow student with a previously exemplary attendance record (not to mention a palpable sexual chemistry with our thrice-divorced professor) burst in midway through Malcolm Jagborough’s plagiarised comments on Old Norse poetry and apologised sweatily for her late arrival. It soon came to light that she has been engaged, for the previous 24 hours, in a liquid battle with The Sun Also Rises, Ernest Hemingway’s spirit-soaked second novel. The rules of engagement were simple: read the book in a single calendar day (not unthinkable if you’re canny with your bathroom schedule) and take a drink every time one of the lead characters does the same.

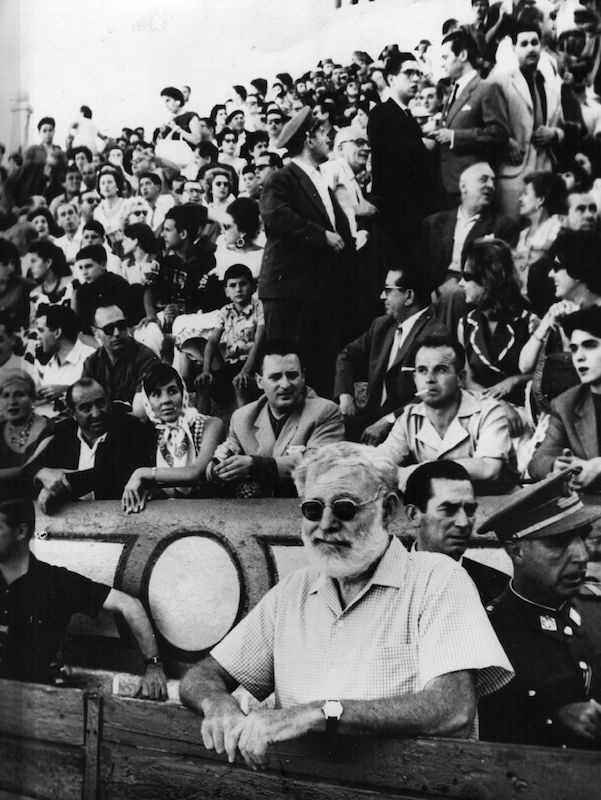

It is a game in the way that the Marathon des Sables is an afternoon stroll. The Sun also Rises name-drops drinks like a particularly cocky fourteen year-old after an exeat spent with his older cousins. In Paris, the book’s protagonists can scarcely finish a sentence or a croque monsieur without calling for a fine a l’eau or a questionably proportioned martini; in the south of France they’re plied with pastis and lager-chased absinthe; in the heat of the Spanish fiesta, meanwhile, the fundador brandy and coarse aromatic wine flow like blood from a particularly slovenly matador. Needless to say, the poor tutee was advocaat yellow and sweating green Chartreuse by the time she’d shanghaied herself into that stuffy backroom.

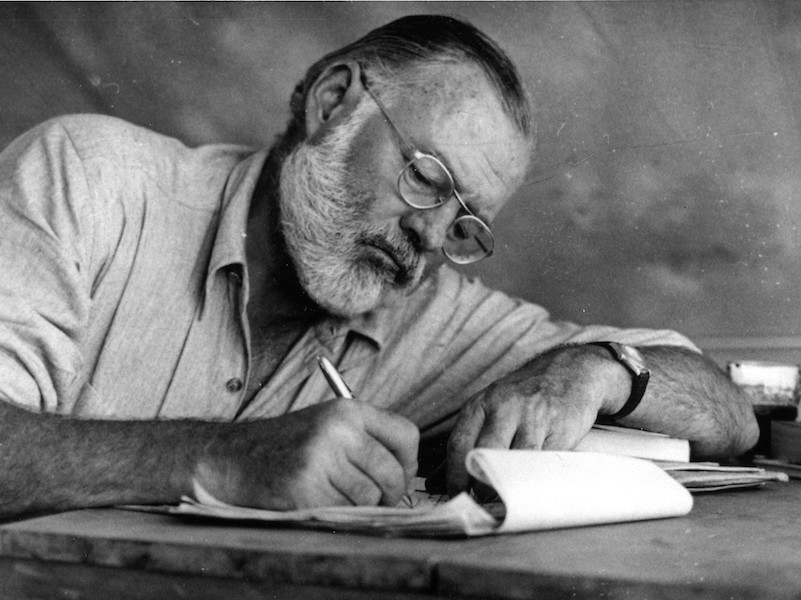

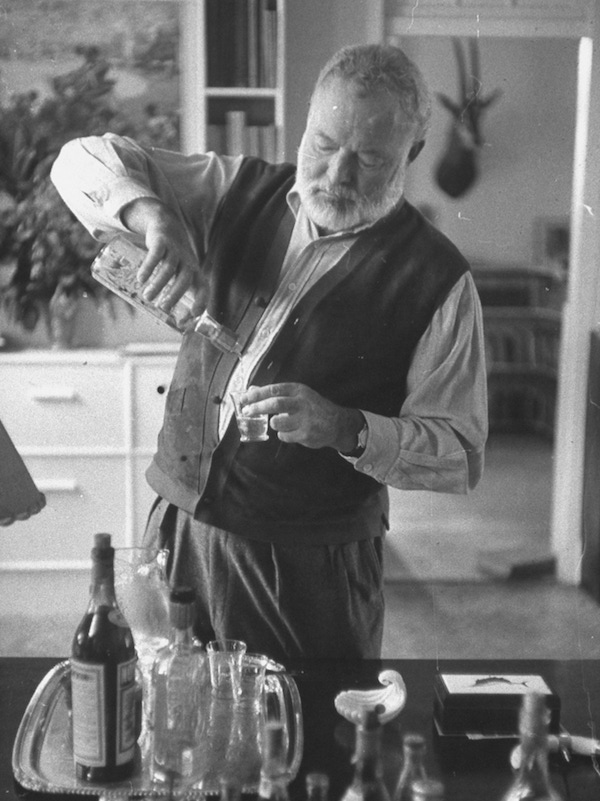

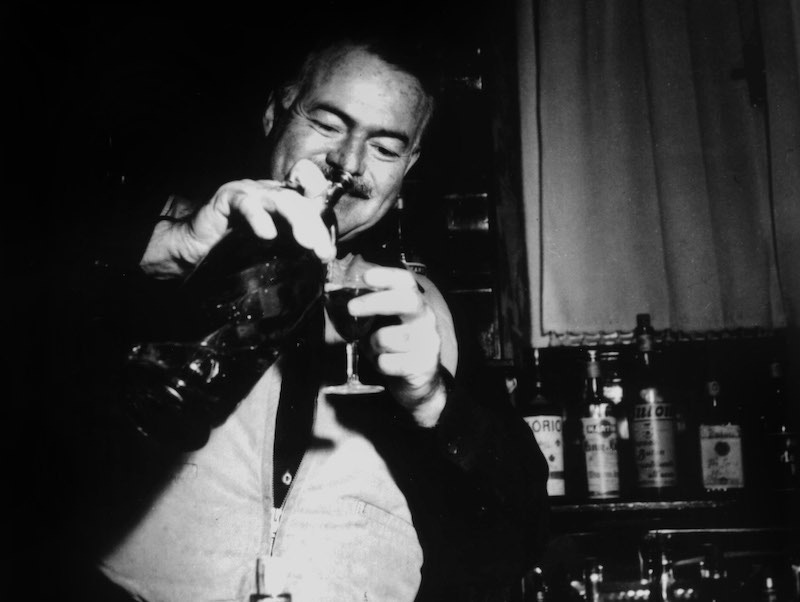

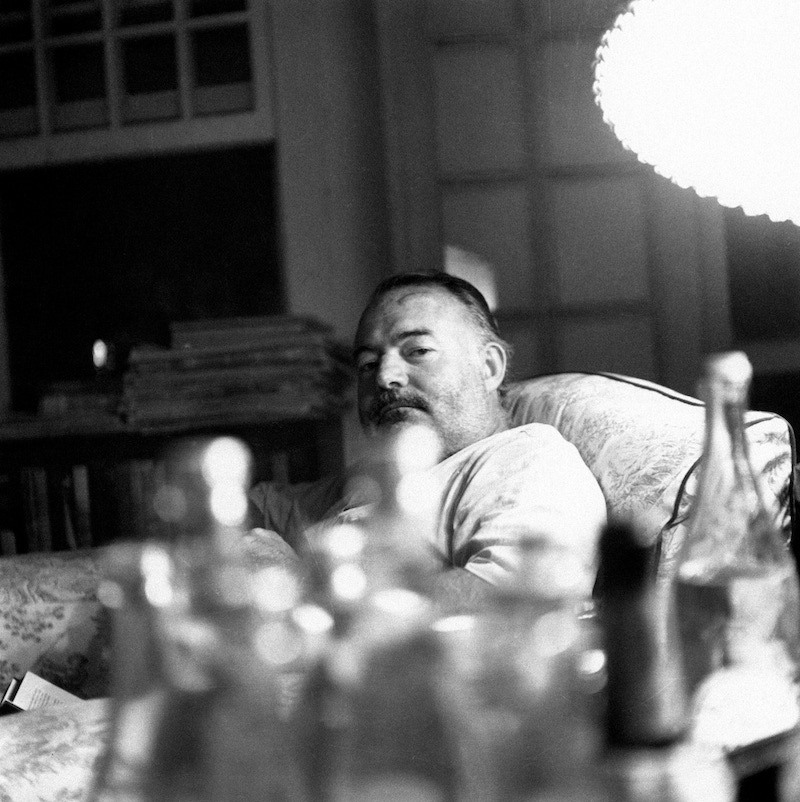

If drinking with Hemingway the writer could jeopardise one’s academic career, drinking with Hemingway the man was an education in itself. First comes Papa H the chemist. A 1933 letter to an executive at Pan American airlines reveals how Hemingway had developed a new way to drink cognac based on 'the principle of carburetion in good petrol engines’ – a sip-exhale-swallow-inhale box step that, he believed, forced the brandy into the lungs in ‘a fine mist; goes into your bloodstream faster’. The writer AE Hotchner, meanwhile, remembers meeting Hemingway in 1948 in a downtown Havana bar, accompanied by two conical vats of frozen daquiri. The Papa Doble had been raised by Ernest in its natural Cuban habitat over a period of several years, and the iteration that sat before them, Hemingway felt, was ‘the ultimate achievement of the daiquiri maker’s art.’ (Hotchner recalls little else from the rum-hazed afternoon, but it is a testament to Hemingway’s prodigious tolerance that the katzenjammered reporter awoke at 6 am to find the old boy rapping at his hotel door, insistent that the two take to the water for a spot of marlin fishing.) Then there’s the freezing of water in tennis ball tubes: just the right size, Hemingway learned through trial and error, to sit in a pitcher of drink without diluting it too much. Perhaps most telling of all, though, is the recent discovery of a mind-numbing scotch and champagne formulation amongst Hemingway’s medical files. The heady tonic is dated to 1951, a time when the writer’s health was at an all time low: it has posthumously been dubbed by Hemingway historians ‘Physician, Heal Thyself.’

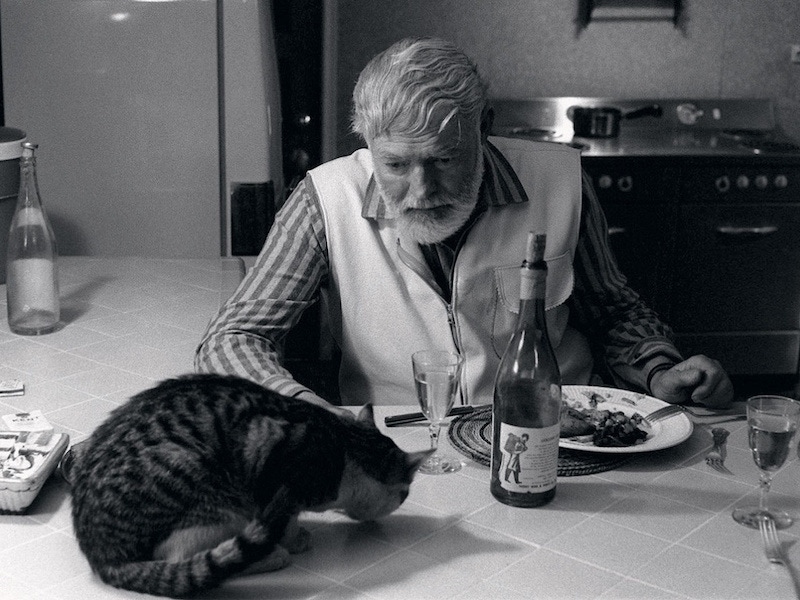

Then there’s Hemingway the anthropologist. A kind of gin-blossomed Livingstone, Hemingway approached new vinous shores with an omnivorous curiosity – though it should be mentioned that he always brought both Campari and Rose’s lime cordial with him on his African safaris, just in case. ‘Hemingway’s going to drink what the locals drink’ says Philip Greene, who recalls – in his niftily titled Hemingway cocktail book To Have and Have Another – how the writer was even induced to battle through a bottle of sake in Japan: "He didn’t like it, but that was what was available." Elsewhere, Hemingway-as-prospector brought to life the Bloody Mary at a time when Vodka was considered some sort of slavic practical joke, and gave equal rise to the practice of chilling cocktail glasses in order to lend the Martini its icepick effect. "It comes out so cold you can’t hold it in your hand." Hemingway boasted. "It sticks to the fingers."

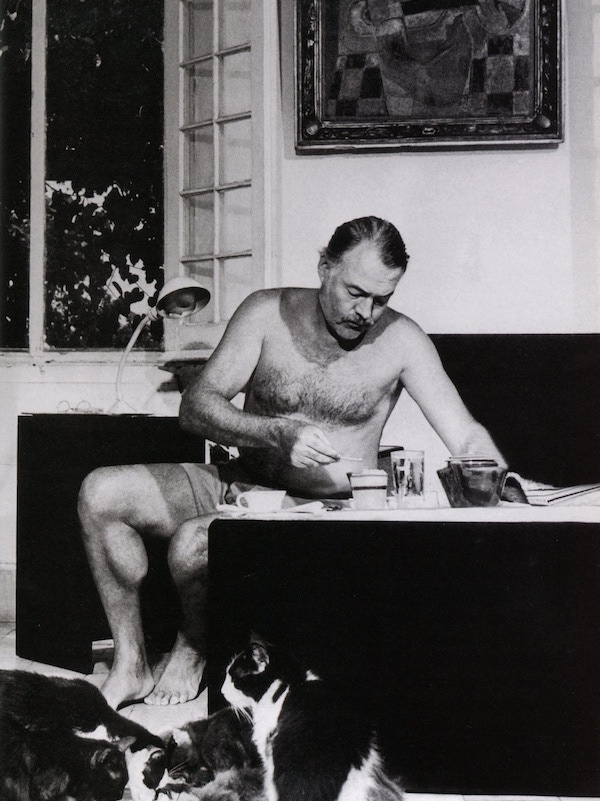

The faculty roster at the Hemingway School of Hard Drinks is not complete, however, without Ernest the resident tutor, a kind of wizened drinking partner, who – out of respect for the institution as much as its attendees – exercised a touching level of pastoral care. Those who hadn’t quite got their head around the subject were offered shoulder-patting inducements (‘I notice you speak slightingly of the bottle.’ he wrote to Russian critic Ivan Kashkin: "I have drunk since I was fifteen and few things have given me more pleasure") whilst fellow inebriates were reminded to keep their livelihood and liver-wrecking separate: "Jeezus Christ! Have you ever heard of anyone who drank while he worked?" James Joyce, meanwhile, was said to exploit this duty of care every time the two encountered drunken belligerence in the cafes of Paris. Jumping behind the prize fighter at a choice moment, the Irishman would cry "Deal with him, Hemingway, deal with him!"

It’s in this persona, in fact, that Hemingway serves up the sagest piece of advice in The Sun Also Rises (the gem appears further into the book, I suspect, then my saturated fellow student ever reached). "Don’t bother with churches, government buildings or city squares. If you want to know about a culture, spend a night in its bars." One imagines Papa could easily squeeze ‘classroom’ into that list. As another academic year rolls around – and as we celebrate 90 years to the month since that novel was first published – it is a school of thought to which any of us might happily enroll.