Home Is Where the Hearst Is: San Simeon Castle

William Randolph Hearst may be a household name, but his household is somewhat as impressive, nothing less than a lavish palace in the hills of California.

It wasn’t enough that his castle would be a monument to grandeur that tipped over into exuberant excess. Even the building of the castle was fraught with wastage. Builders would slave away for weeks creating some part of the structure, only for the visionary - or crazy - paying for it to decide on a whim that it wasn’t right and insist it was torn down. One fireplace was ripped out, repositioned, then a few months later put back in the original position. And there were many fireplaces: 41 in all. This castle covered some 80,200 square foot of living space. It had 56 bedrooms, 61 bathrooms, two pools, a movie theatre, tennis courts, an airfield and the world’s largest private zoo - with 300 different species - and was all 1600 feet up atop a hill. Such was the gargantuan nature of the project that completion ran a mere 27 years over schedule.

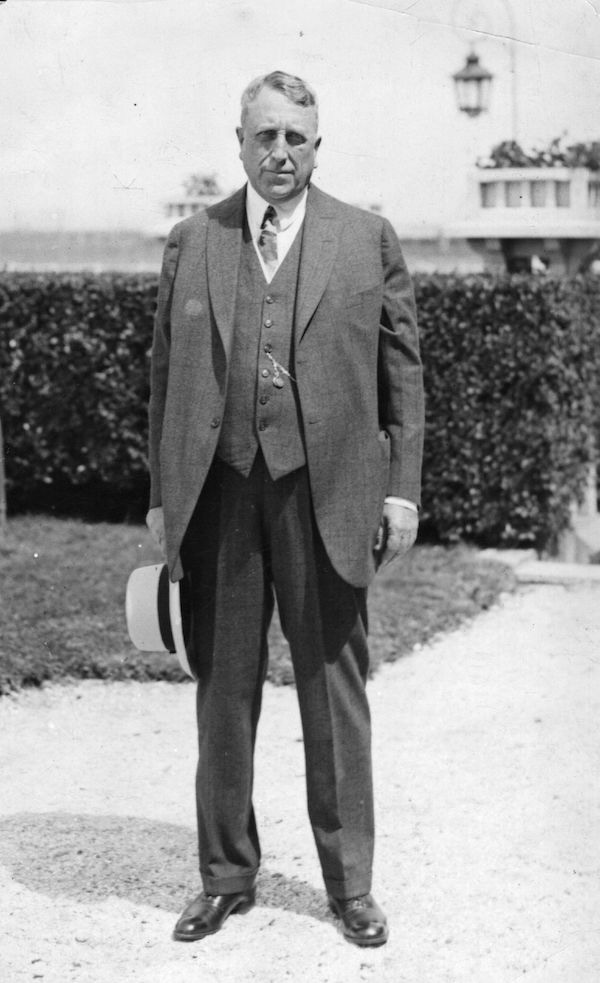

But then the visionary behind this castle was no ordinary man - he could indulge his excesses. William Randolph Hearst - the larger-than-life inspiration for Orson Welles’ larger-than-life Citizen Kane - died 65 years ago this year after a lifetime of getting exactly what he wanted, and getting it now. There was a good reason why he came to be known as The Chief. “I would like to build something up on the hill,” Hearst had once said of his castle. “I get tired of going up there and camping in tents. I’m getting a little old for that. I’d like to get something that would be more comfortable.” He wasn’t kidding.

Such was Hearst’s impatience that everything in the castle’s 127 acre grounds, including 1000 rose bushes, was planted fully grown. The flower beds were ripped up and replanted not annually, with the seasons, but four times a year. Indeed, construction on the castle would begin in 1919, the very year Hearst inherited $19m ($272m in today’s money), together with 130 square miles of Californian coastal ranch land of almost immeasurable real estate value.

Yet while the castle would go on to be filled with art works of a standard only otherwise seen in national museums - ancient statuary, Flemish tapestries, Old Masters - Hearst’s spending was not altogether hedonistic. Within months of coming into the money - money accrued through his father’s publishing empire - Hearst himself had bought 28 newspaper companies and 18 magazines. His running of these would in time see one in four Americans daily reading one or other of his papers and his wealth increase ten-fold. That would only allow the spending to continue.

Hearst would certainly have been delighted by the news this September that a second mansion of his, in Beverly Hills, was listed as the most expensive property for sale on the US market, yours for $195m. Who knows what his many, many other properties - among them the five storey penthouse on New York’s Riverside Drive - would be worth today? That started out as a mere three floor rented home, by the way. When the building’s owner refused Hearst’s demand for another two floors, Hearst just went ahead and bought the entire building. When that was deemed too small to host his friends, he built a hotel for them down the road. Cary Grant lived there for the best part of a decade.

Even Hearst’s newspaper proprietorship had an air of excess to it. Hearst can in part be credited with the invention of sensationalist tabloid journalism. If there was an outrageous headline that would inflame his readership, he printed it. When the illustrator Frederic Remington requested permission to return from Havana, where he’d been stationed in expectation of a conflict that hadn’t come, Hearst’s reply was only half-joking: “Please remain,” he telegraphed. “You furnish the picture and I’ll furnish the war.” It was a fitting response for a man of often grand reactionary tendencies that may have become all too familiar following a recent election campaign - isolationist, racist (at least towards Mexicans, proposing an all-out US invasion of Mexico), even in the end flirting with fascists, with Hearst actually attending the Nuremberg rally of 1934 and running paid-for columns by both Hitler and Mussolini. Hearst ran for president as well.

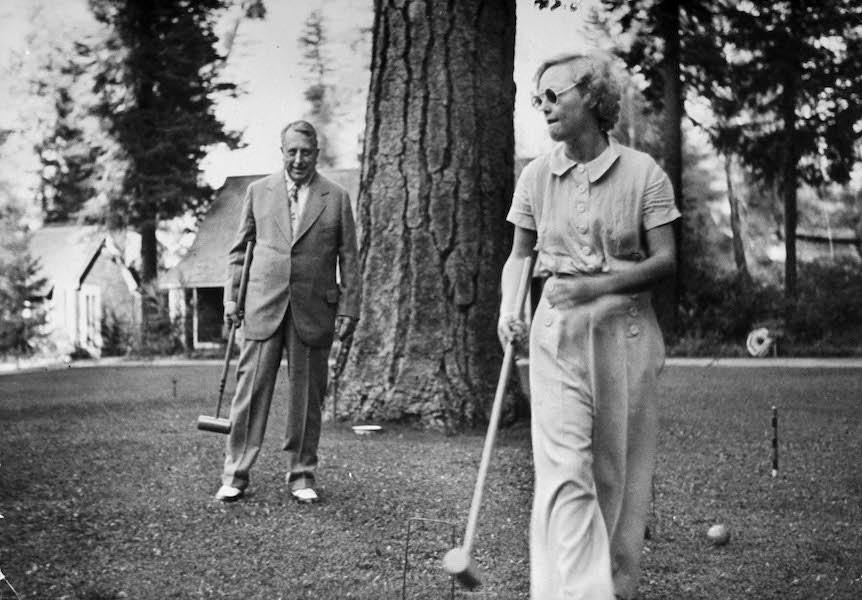

Such was the enthusiasm with which Hearst would spend that he often came close to going broke. At one point - compounded by the crash of 1929 and the depression that subsequently affected all of his business interests - he accrued debts of $87m. He would take out loans to allow business to survive, and the spending to go on, and when foreclosure was imminent, on one occasion his mistress, actress Marion Davies - 34 years his junior - sold her jewellery and stocks to give him a lifeline million dollars.

He bounced back, of course, if not quite to the former glory. The castle, its contents and grounds - just part of the $200m estate he left when he died - went to Davies in his will. This itself a masterwork of overkill, running to 125 pages, with nine bewildering codicils, each of which affected changes made by the ones proceeding - like so many misplaced fireplaces. Remarkably, Davies sold the castle back to Hearst Corporation - for one dollar. Perhaps proving that there are some things you can’t buy, Davies stated that, despite their many naysayers, her relationship with Hearst had been one of love. She didn’t want the money. It was of no use to her. How mismatched the couple must at times have seemed.