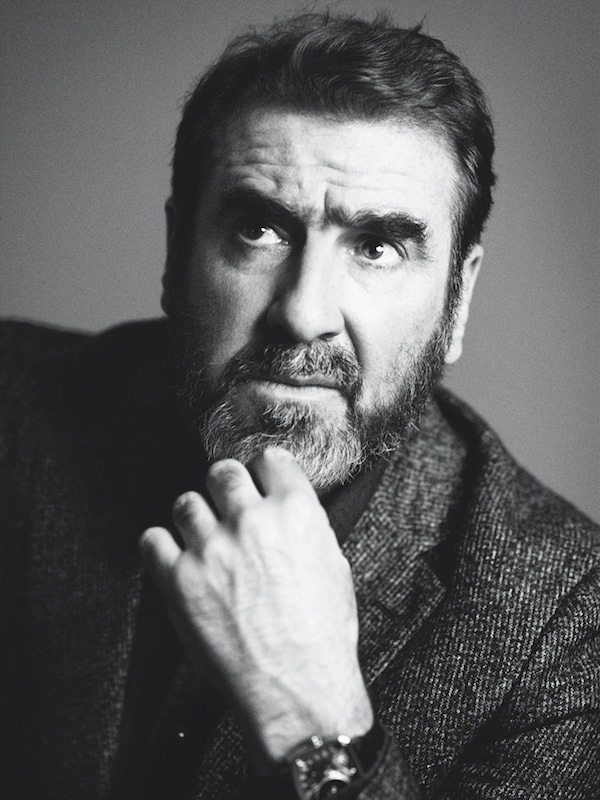

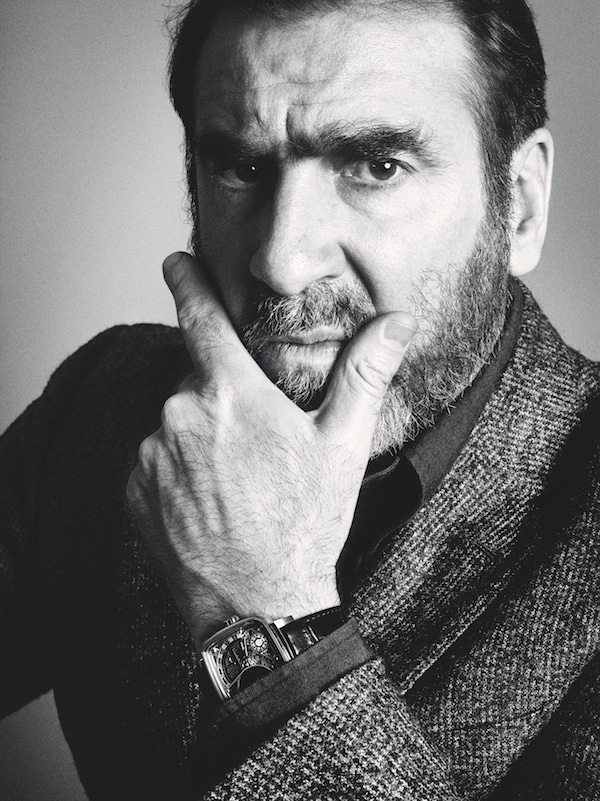

La Vie Beau De La Vie: Eric Cantona

“Design isn’t all about aesthetics — I like it when it means something, opens some doors.”However much thought and zeal he puts into it, design will never be the discipline for which Cantona is primarily known. Nor will his acting, poetry, art, political activism, intellectual leanings, and certainly not the wry self-awareness to which many people — especially those who have chosen observation as a career, curiously — continue to appear wilfully oblivious. The segment of his life that made Eric Cantona a household name dominated nearly three decades of his five on the planet, and began in the late sixties in his place of birth, Les Caillols, in the 12th arrondissement of Marseille. Legend has it that Cantona grew up in a nine-square-metre hillside cave. The reality is more prosaic. His grandmother discovered the grotto in question, nicknamed it La Chambrette, and decreed that it would be used for shelter while her husband, a Sardinian immigrant and a stonemason, built the house that now nestles among the pines on the hill above it (Cantona’s maternal grandparents were also immigrants — Catalan exiles from Franco’s Spain, who crossed the Pyrenees on foot). It was on the rugged gradient stretching down from this self-built family home that the young Cantona honed his skills, playing football compulsively with his brothers, Joel and Jean-Marie, encouraged by their father, Albert, himself a useful goalkeeper. According to the French football journalist Philippe Auclair’s book Cantona: The Rebel Who Would Be King — one of the most exhaustive and deft sports biographies you could hope to read — so devoted to the game were the brothers that whenever a misdirected kick went hurtling down the hill, they’d crumple old newspapers into a sphere and carry on until the ball was bowled back up by a neighbour.

Cantona has described the exceptional football career that unfolded later on as an attempt to recapture the moment his infant hands first plucked a ball from the gravel and weeds of his childhood home — “Maybe… the sun was shining, people were happy, and it made me feel like playing football” — and his career certainly wasn’t short of Proustian flashbacks to that moment. Having made his debut at local club Auxerre aged 17, Cantona arrived at Manchester United eight years later — via Martigues, Marseille, Bordeaux, Montpellier, Nimes and Leeds United — and promptly sparked the most successful period in the club’s history.

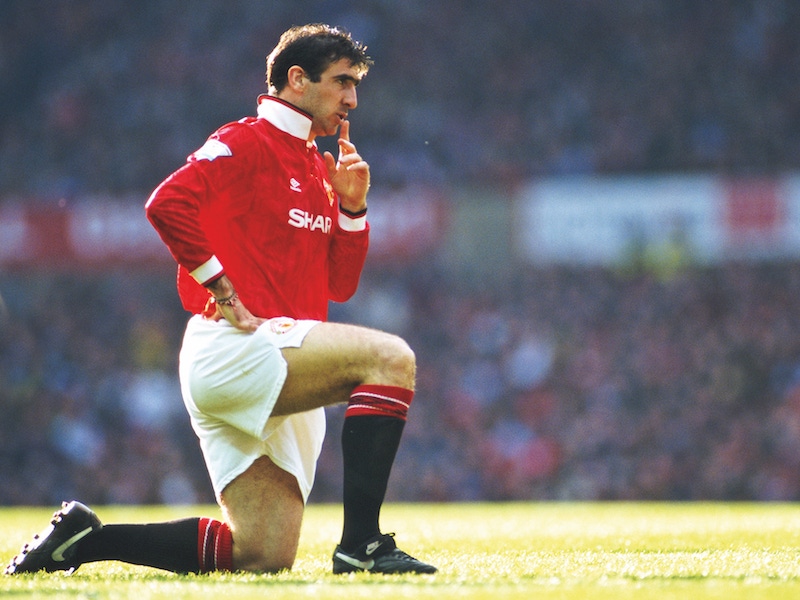

Strong and graceful, with almost supernatural vision, he opened up defences so effortlessly that United’s manager of 27 years, Sir Alex Ferguson, nicknamed him the Can Opener. Cantona’s bluster, imperviousness and creativity infected a generation of young players — Paul Scholes, David Beckham and Gary Neville among them — and United won four titles in five years. He became a near-deity, and his goal celebration — one arm thrust aloft, fist clenched, collar upturned, chest inflated — is etched more deeply than ever on the memories of a beleaguered United fanbase currently reliant on nostalgia.

Eventually, though, those nuggets of déjà vu began to lose their lustre, and a week after lifting the Premier League trophy at Old Trafford in 1997, following a Champions League semi-final defeat to Borussia Dortmund — a bitter blow to him — Cantona announced his retirement just short of his 31st birthday, with a year left to run on his contract. Forays into beach football and a brief spell as the New York Cosmos’ director of soccer (which ended in a legal dispute over unpaid wages) followed, but today, Cantona’s interest in football is only a passing one, to say the least. We were tipped off by the publicity team that organised our photoshoot and interview that grilling Cantona on the subject would yield little; during banter with our photographer he expresses a keen admiration for Manchester City’s Spanish midfielder David Silva, but otherwise shows little interest in, or knowledge of, the modern game (I have to tell him who manages Tottenham Hotspur these days)...

Read more in Issue 46, available on newsstands now, or subscribe here.

Fashion Stylist, Jo Greszczuk

Grooming, Kazuko Kitaoka.