Le Philosophe Provocateur

Prolific not just between the sheets but also in terms of his bountiful polemics on the human condition, Bernard-Henri Levy remains, at 65, a uniquely French phenomenon: a modern celebrity thinker.

There are few philosophers famous enough to be elevated to the status of a brand, but Bernard-Henri Lévy - or BHL, as he's affectionately/derisively known as in his native France - is one. He's the exemplar of a uniquely French phenomenon: the preening, pugilistic public intellectual who's as likely to be found in the pages of Paris Match, confirming or denying the latest rumours of an affair with a starlet or heiress, as in more learned journals, refuting the writings of Kant or berating governments for inaction in the face of the Syrian conflict or the renewed impetus of France's right-wing National Front.

'Philosopher, publisher, novelist, journalist, filmmaker, defender of causes, libertine, and provocateur, he is somewhere between gadfly and tribal sage, Superman and prophet,' is how former Editor-in-Chief of Vogue Paris, Joan Juliet Buck, in a Vanity Fair profile, once described the man who has breezily declined to accept the Légion d'Honneur - France's highest decoration - on an almost annual basis. And, although he represents no party and holds no official job or elected office, BHL's visage hovers, omnipresent, over French national and political life: he's embarked on a government mission to Afghanistan; issued written treatises on international affairs (he's authored more than 30 books); defended his friend, the former IMF chief Dominique Strauss-Kahn, over the accusations of attempted rape brought by a hotel chambermaid in New York; and curated an exhibition, titled, with characteristic immodesty, 'Adventures of Truth - Painting and philosophy: a narrative', at the Maeght Foundation on the Côte d'Azur.

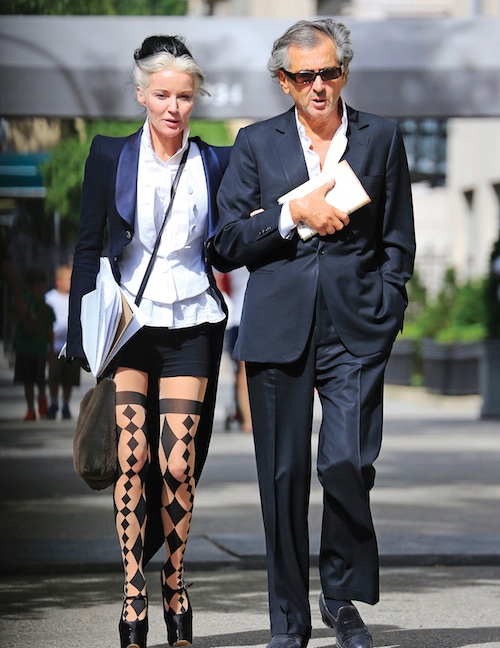

The BHL visage is a chiselled, well-groomed one. At 65, he still boasts a luxuriant, nonchalantly groomed grey mane suited to a polo player, and he favours fitted dark suits over raffishly unbuttoned white shirts, revealing an ample expanse of firm, creamy chest. He's been compared to Charles Baudelaire, Victor Hugo, Émile Zola, André Malraux, TE Lawrence and King David. Arielle Dombasle, his wasp-waisted actress wife, said that the first time she saw a picture of BHL, she thought he was Jesus Christ. But the man himself sort of demurs: 'I am someone who thinks he can influence things and do it with fire and passion and energy, and then the other side of me speaks up and says, 'Just write.'' He attracts adulation and opprobium in equal measure. One of his best friends, the painter Jacques Martinez, says: 'He's handsome, he's talented, he's rich, he has a beautiful wife - of course they hate him.'

As to BHL's thinking - the finer nuances of which can often be obscured behind the lover-and-fighter sound and fury - it's essentially iconoclastic, a product perhaps of a background rich in outsider status. He was born in French Algeria to a wealthy Algerian Jewish family who moved to Paris a few months after his birth. His father, André, was the multimillionaire founder and manager of a timber company; regarding his family fortune, BHL has said, 'I knew when I was 20 that I'd never have to suck up to anyone.' His philosophy degree came from the elite École Normale Supérieure, where he was taught by the likes of Louis Althusser and Jacques Derrida, and he became famous as the young founder of the New Philosophers. Disenchanted with the communist firebrand rhetoric surrounding the May 1968 student uprisings in Paris, he denounced Marxism and posited that the Old Testament could be a guide to a humanistic socialism (which, he says, 'turned some of the Jews and most of the anti- Semites against [him]').

He's probed the running sore of French Fascism and the rise of the extreme right, helped found an anti-racism group (SOS Racisme) to empower the black and Arab populations of France against extremism, and has never come across a fight he wasn't already spoiling for: 'I am against the cult of common sense,' he says. 'Common sense is rarely right.' He cut his skirmish- ready teeth early, beginning his career as a war reporter for Combat, the underground newspaper founded by Albert Camus during the German occupation of France, and has brandished his intellect in virtually every war zone since, from Bangladesh (where he covered the Liberation War against Pakistan) to Bosnia (where he was one of the first foreigners who got into the besieged Sarajevo) to Afghanistan (where he shipped radio transmitters to favoured warlords) to Sudan (where he agitated for action over the crisis in Darfur). In his book Réflexions sur la Guerre, le Mal et la fin de l'Histoire (Reflections on War, Evil and the End of History), he wrote that, rather than use the novel to 'explore the unknown possibilities of existence', he does reporting: 'It's into real life, not into fiction, that I have gone, for a long time now, to find my new perceptions.'

The other public perception of BHL himself - that of libidinous libertine - has been as assiduously burnished as his combat credentials. He has written of his own more-than- louche early years in Paris, involving 'thefts, holdups, assaults on virtue', as Buck summarises it in Vanity Fair. During this period, as one friend said, 'his models were more Bonnie and Clyde than Beauvoir and Sartre'. He's been married three times, but has put as much, if not more, energy into his conquests as his convictions: 'He'd go to a dinner party and know that he'd sleep with the hostess within the week,' recounted one friend, adding, 'He could start off the evening with one woman, go sleep with a second one, and join the third in her bed at five in the morning.' As BHL himself once admitted, '[I was] good at duplicity, and all kinds of women attracted me. And because I sleep only four hours a night, I have a little more time to live than most people.' (Perhaps to exalt his licentious image, BHL named his eldest daughter Justine- Juliette, after two of the Marquis de Sade's heroines.)

And, living is something that BHL is ostentatiously good at. He never learned to drive, so a chauffeur conveys him around Paris in a Daimler sedan. When not at home in Montparnasse, or working at the Colombe d'Or, the rustic hotel in Saint- Paul-de-Vence, with walls lined with Braques and Picassos,

he hangs out in his Moroccan palace in Marrakech, built for the city's Pasha in the 18th century and subsequently owned by John Paul Getty Jr. and Alain Delon (from whom BHL bought it), complete with a harem where Marlon Brando once whiled away six months. Here, BHL writes while Dombasle goes over scripts. The pair met at one of BHL's book signings, and he went on to cast her in the only movie he's directed, Le Jour et la Nuit (Day and Night), which Cahiers du Cinéma deemed as the worst French film in decades. BHL and Dombasle conducted a long affair before eventually marrying in 1993; he says he was 'thunderstruck' by her, friends say she understands his need to be loved and to be told he's loved, and the relationship has withstood his subsequent long affair with Daphne Guinness, the British socialite and muse of Karl Lagerfeld and Alexander McQueen.

And so, onward BHL goes, braving a snipers' alley here, appearing in an art installation alongside Sharon Stone there, adding to the gaiety and the gravity of France in almost equal measure. It would, of course, be sacrilegious to reduce the credo and tenets of this impeccably buffed freethinker and scourge of the hidebound to a single line, but, if tempted, it's hard to top the dictum coined in an article about him a few years ago: 'God is dead,' it quipped, 'but [his] hair is perfect.'