Samuel L. Jackson: The Path of The Righteous Man

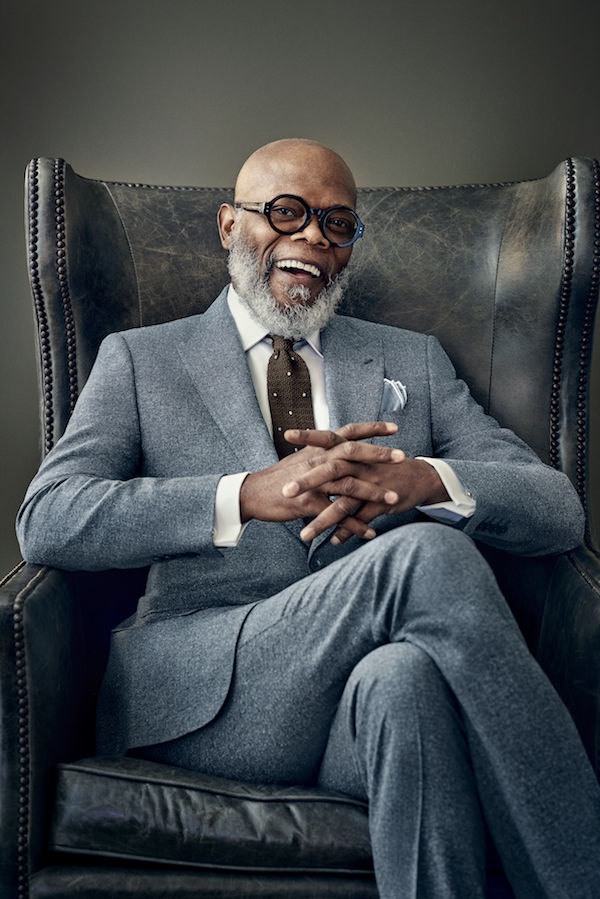

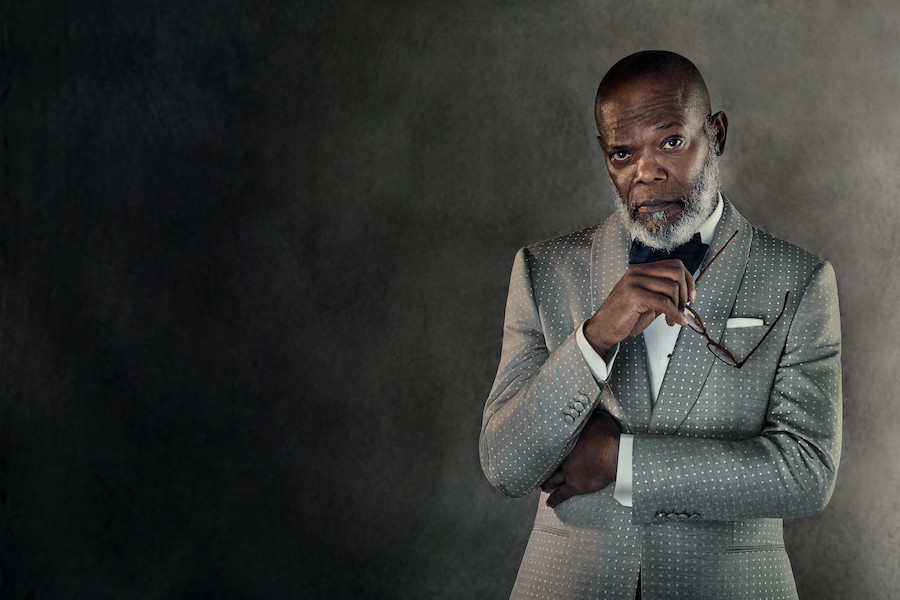

After he first exploded as if fired by a cannon onto the film-going-public’s consciousness as Jules Winnfield in Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction, a performance considered by many to be one of the greatest works of acting in arguably the most entertaining movie ever made — for which he won a BAFTA award and Independent Spirit award — Samuel L. Jackson has enjoyed a career characterised by consistent success and longevity. Yet even more noteworthy is the way in which he has crafted his career while never compromising who he is. He is outspoken on his beliefs related to race issues and police violence in the United States; he is critical of the current generation’s obsession with fame; and he is dedicated to raising awareness of cancer among men because he understands that men often don’t like to admit they have problems. When The Rake met with him in Telluride, in between filming Quentin Tarantino’s The Hateful Eight, we found him to be a man of considerable largesse. He was generous with his time, with his energy and with his thoughts, and amenable throughout both our interview and photoshoot — at one point even encouraging our brilliant photographer Tomo Brejc, as Brejc struggled to articulate the expression he wanted Jackson to wear, to “Speak, motherfucker, speak!”

Who is Samuel L. Jackson? Aside from cinema’s greatest commercial success story, he is considerate, thoughtful, sincere and, very possibly, the coolest man on the planet.

Do you feel that contemporary culture’s obsession with fame conflicts with the seriousness of acting as a craft?

I still think that acting is a craft. That it is something people need to respect and it is much more than just the fame aspect of it. The things we learned to do on stage or the things we learn to do from beginning to end are a lot more interesting than going to work and shooting two and half pages a day. Sure, film pays more (than theatre), but it is a director’s medium. He goes into a room and he takes the little pieces of film and puts them together and creates the story. It might look like what you intended it to look like, and it might not. So I still respect the theatre in a very real kind of way. I miss it. I did a play two years ago and that was great. Getting back into that flow of having to do something eight times a week is great. Every performance there’s a new audience and they are there and they are alive, so you’ve got to show up and do it. People can fix your performance if you’re doing a movie — they can even dub you over with someone else’s voice. But today, with the fame machine that’s out there, people tend to want fame over being respected or having a long career.

I got my sense of style from my mother. She was a buyer so she would go to shows. And then she would come back with samples and I would dress in those samples. So when I went to school I would always be dressed in the style that people would be wearing the next year, because fashion works in advance — but the other kids, of course, wouldn’t know that. And because of that I never fitted in. I was wearing a certain style one year before anyone else and the other kids would laugh at me. And I would think, ‘Just you wait, motherfuckers, I’m going to have the last laugh’.

You have stated that when you got over your addiction, you’ve never feared about relapsing because everything good that’s happened to you is a result of sobriety. Can you tell us about the power of your sobriety?

I think sobriety is different for everybody. I always say that my career trajectory changing is a direct result of me getting sober. I guess having clarity of thought and clarity of purpose helped in that way, but people could also make the argument that I traded in one addiction for another when I started going to work. Work motivates me; I like being different characters every day. Having a purpose and understanding what that purpose is, and being able to make choices that keep me interested, are very important things. Now I get to make choices, and I guess I make sober, informed choices. They are choices that interest me. I do things that I want to see myself in. I’ve always wanted to do different genres of movies. I do things that intrigue me in terms of where I can go with a character and how far I can push that envelope.

There’s a great scene in Changing Lanes when you just stare at a shot of Scotch and where you can really see your struggle over alcohol. Has your sobriety ever been challenged?

The most amazing thing about that particular scene was that we were in a bar in New York. And the guy who was playing the bartender must have been an extra. And he actually poured a shot of Scotch and put it in front of me. They usually put ice tea into those glasses. Now I haven’t had a drink since 1990, and I was sitting there thinking about this and I smelt the liquor wafting up into my nose and I was like, ‘Oh shit, this is real. This is a real drink.’ And I was remembering how good this shit tastes. I didn’t say anything, I kind of just let the shot play out, and Roger (Michell), the director, was like, “Wow, your face was just amazing in that scene”. I replied, “Well, that was real Scotch”. He said, “What? Take that away immediately.” I said, “It’s OK, I’m not going to drink it, I just had an interesting sense memory for a minute”. It changed the reality of what was going on in that scene in that moment. That was a great cinematic experience doing that film, because Roger is such a great director.

It’s true that I overcame I childhood stutter, though not necessarily through the prolific use of the word ‘motherfucker’. But it was definitely one of the words I said a lot, and I didn’t stutter when I said it. I would practise saying ‘motherfucker-motherfucker-motherfucker’. I could do that pretty quickly and do it when skipping rope, sort of chant it. But I really overcame stuttering by learning to breathe, to calm down.

In July last year, New Yorker Eric Garner died after a police officer put him in a chokehold, an action prohibited by the New York Police Department. (Law enforcement officials say it was a headlock.) You took a public stand against police violence and were attacked for it. Can you tell us why you took this stand?

All my life I’ve had to learn to live in a world that is a dangerous place, with me understanding that my life is expendable. That it could be snuffed out in any instant — and that the people who did it could get away with it — has informed the way I deal with the world. I was in London when Eric Garner happened. I was not surprised. He was a big kid. You got a cop that is used to being in this particular community. The fact that he’s got a badge and a gun gives him some feeling of superiority, that he can do what he wants. But that cop is also pretty much afraid of all these people he is encountering every day. Before he says hello to them he unsnaps his holster flap and puts his hand on his gun. But there’s still a way that you deal with cops so that certain things don’t happen. Look at when (Professor) Henry Louis Gates got jacked up on his own porch coming home from a trip to China researching Yo-Yo Ma’s ancestry, and he didn’t have his key and he broke into his own house. The cops show up and because he gives them some lip about it, they arrest him even though he’s already proven that it’s his house. (In July 2009, Harvard University professor Gates was arrested at his home in Cambridge, Massachusetts, by a police officer responding to a report of men breaking and entering the residence. President Obama said of the incident: “I don’t know, not having been there and not seeing all the facts, what role race played in that. But I think it’s fair to say, number one, any of us would be pretty angry; number two, that the Cambridge police acted stupidly in arresting somebody when there was already proof that they were in their own home; and number three, what I think we know separate and apart from this incident is that there’s a long history in this country of African Americans and Latinos being stopped by law enforcement disproportionately.”)

So racist police are still very much an issue in America?

I’ve heard white kids say terrible shit to cops where I was just standing there going, “So when’s the cop gonna knock him out?” But because he’s white it never happens. I’ve been with black kids who said much less and they got smacked in the face. So there are certain things [as black people] that we have to understand. We understand that cops are afraid and that backed into a corner the first thing they are going to do is shoot first and worry about sorting it out later. So you teach your kids. I told my daughter, If a cop stops you, say, “Yes sir, no sir” — be polite. Make sure he can see your hands at all times. Don’t do anything to provoke him. And at a certain point, when the cop realises who you are, it might get worse. It’s definitely not going to get better. Come on, you’re the daughter of some rich black movie star. If they found out who my daughter is, they’d go, “Oh, he already said some bad stuff about the cops”.

Read the full story in Issue 39 of The Rake. Contact subscriptions@therakemagazine.com or subscribe here.