The Comeback: Matthew McConaughey

Ed Cripps explores the career of the Texan heartthrob Matthew McConaughey, and while it's fluctuated between mediocracy and Oscar-stardom, he's a fully fledged member of Hollywood royalty.

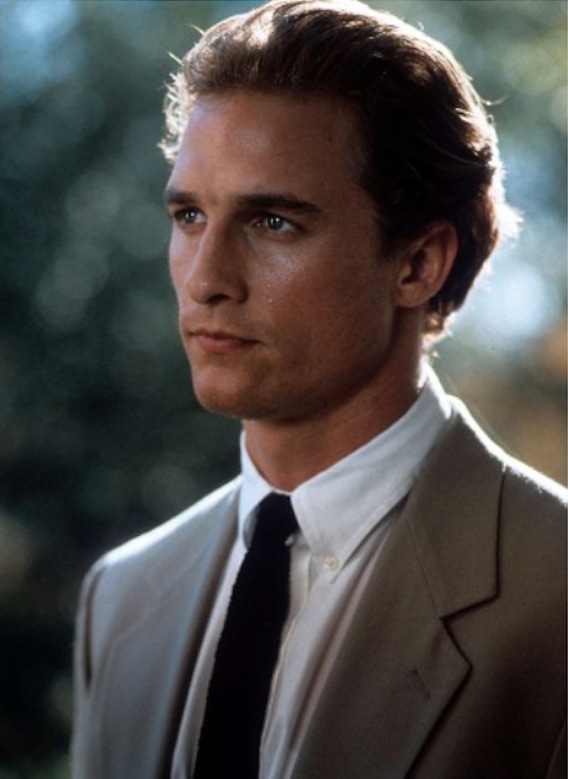

Of the recent Hollywood comebacks (Ben Affleck, Michael Keaton and now, unfathomably, Mel Gibson), Matthew McConaughey's beguiles the most. In her excellent piece ‘The McConaissance’, New Yorker journalist Rachel Syme describes the actor’s reinvention as “a clever (and purposeful) undoing of a mythos and the embrace of a more authentic McConaughey, even if that reveals something grimy and sad under the creamy Texas accent”: his new persona is “casually weird and much darker than expected”. With those lemon blue eyes and a voice as hummingbird-light as ravine-deep, he has always shimmered with charisma, but the mind has finally outshone the physique.

At 23, he won the definitive role of his early career as Wooderson in Richard Linklater’s Dazed and Confused after impressing the film’s casting agent on a boozy night out (“I thought this was a bar!”, bellowed McConaughey after they were ejected). Wooderson is the oily campus life-guru, full of glib wisdom and proud that he gets older as the high-school girls stay the same age. After he played a defence lawyer in John Grisham adaptation A Time To Kill opposite Kevin Spacey and Samuel L. Jackson, a meaty role with the requisite heroic closing argument, Vanity Fair anointed him the new Paul Newman.

The world was his, and yet he soon became best known for amiably forgettable rom-coms like The Wedding Planner, How To Lose A Guy In 10 Days and Failure To Launch, not to mention his abs (in 2005, he was voted the Sexiest Man Alive). Detractors accused him of complacency and vanity - was he as content in the stupor of escapist fantasies as his character in Dazed and Confused? Yes and no. For a young actor mindful of how quickly the Hollywood wind can change, it was pragmatic, invaluable experience. A turn as an agent in Tropic Thunder showed a glimmer of effervescence. Then, after filming Ghosts of Girlfriends Past, he made a conscious decision to “unbrand”. Work dried up for a while, but in his own words he suddenly became “a new good idea for some good directors”.

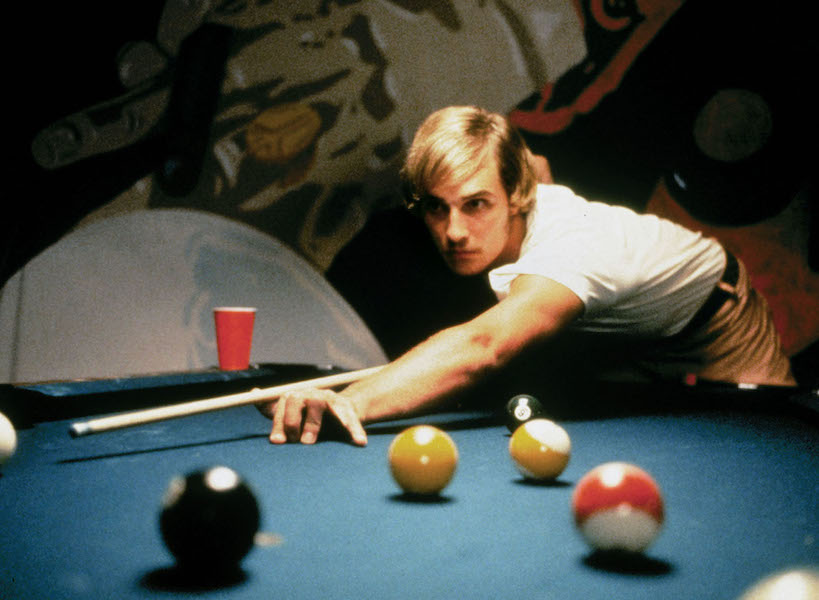

What directors they were. He terrified as a murderous detective in William Friedkin’s Killer Joe, glistened as an Arkansas Magwitch in Jeff Nichols’ gorgeous Mud, reunited with Richard Linklater as a Wheel of Misfortune-spinning DA in black comedy Bernie and (most satisfyingly of all) dismantled his studmuffin persona as a weary stripper in Steven Soderbergh’s Magic Mike, a tragicomic, self-referential examination of selling one’s body for dollar bills.

Then came three of his most iconic roles within the space of a year. To play homophobe-turned-AIDS activist Ron Woodruff in Dallas Buyers Club, he lost 38 pounds, reworked prejudices and won an Oscar. He mesmerised as a senior stockbroker in Martin Scorsese’s The Wolf of Wall Street, incorporating his own chest-beat warm-up exercise into a lunch scene with Leonardo DiCaprio, advocating more frequent masturbation (“You gotta feed the geese to keep the blood flowing”) and spouting home-truths about Wall Street that could equally apply to Hollywood (“Nobody knows if a stock is gonna go up, down, sideways or in fucking circles”). The fullest expression of his faculties was True Detective opposite his EDtv co-star Woody Harrelson: Rust Cohle was rangy, soulful, minimalist, unpredictable, eccentric and disquieting, the Southern Gothic apogee of his career in a medium that gave him room to riff.

Now a prestige A-lister, he brought brains and pathos to Christopher Nolan’s three-hour sci-fi epic Interstellar (the scene where he reads 23 years-worth of messages from his children shows a new maturity). He also takes risks: Gus van Sant’s The Sea of Trees was booed at Cannes and made under a million dollars at the box office, but there’s a nobility in the intellectual ambition and McConaughey’s defence of it since.

In real life, McConaughey sails close to pretentiousness. One of the people he thanked in his Oscar speech was himself. His Nicholas Winding Refn-directed adverts for the Lincoln Motor Company have been satirised on the likes of SNL, South Park and Ellen Degeneres for philosophies like “sometimes you gotta go back to actually move forward”. But this couldn’t be more truthful to McConaughey’s own narrative, and now he's jump-started a car company’s fortunes in a similar way to his own. Refreshingly unsnobbish about adverts, their pay checks allow him to do weightier, "littler" films and, as a man whose favourite book is Og Mandino’s The Greatest Salesman In The World, he clearly loves to sell (he has just been made creative director of Kentucky bourbon distillery Wild Turkey). Arrested as a 30-year-old in 1999 for naked bongo-playing under the alleged (but unfounded) influence of weed, he is now married to Brazilian model Camila Alves and a father of three who teaches at the University of Texas (his alma mater) and campaigns for multiple charities.

If you split Matthew McConaughey's CV pre-2009 and post-2011, they could (and normally would) come from two different actors, but how unimaginative to assume they can’t be reconciled in one performer. Perhaps a Hollywood career, like time in True Detective, is a flat circle. Or maybe it’s like the tesseract in Interstellar, a smaller cube inside a bookshelf-lined larger cube, commerce within arthouse, young at the heart of old. McConaughey once told Esquire that “at the end of your life, all the things you thought were periods, they turn out to be commas. There was never a full stop to any of it.” Like his Dazed and Confused co-star Ben Affleck, he has mastered the art of the comma, the free-flowing sentence, and seems more fluent than ever. No coincidence that his finest character, Rust Cohle, articulates that confidence the best: “I know who I am. And after all these years, there’s a victory in that”.