The Miami Vice Effect

How the Michael Mann-helmed TV hit turned gauche into gold, shaped 1980s men’s style and gave a facelift to a city on the side.

Often cited as the ultimate example of life imitating art, Miami Vice utterly reshaped the city that inspired it. Over the course of its five-season, 112-episode run from 1984 to 1989, Vice rehabilitated the Floridian burgh’s “global image from bland retirement village to a sexy and shady metropolis,” in the words of local organ, the Miami Herald.

“It showed Miami as the capital of cool. It oozed glitz and glamour. Fast boats and flashy cars… Miami Vice had it all,” said the Christian Science Monitor. “Too bad the city itself back then (in the ’80s) had a murder rate more than quadruple the national average. Tourism revenue was at rock bottom… But when Miami Vice was cancelled, a funny thing happened to the real Miami: It started to look more and more like the TV show.”

The influx of ill-gotten gains made by exactly the type of ‘contraband entrepreneurs’ who were Miami Vice’s stock in trade fuelled rampant development in the city, with the flow of cocaine money trickling down to car dealers, nightclubs and bars, five-star hotels, restaurants, lawyers, realtors and various other upper-echelon service providers, plus purveyors of all manner of luxury products (Miami was America’s top market for Swiss watches for much of the era). Flush with narco dollars, the newly affluent city was given a facelift to match the slick, colourful look show impressario Michael Mann has fastidiously created on screen. (In some cases, Miami Vice was directly responsible for the restoration. Producer Mann — who’d decreed a ban on earth tones and tattiness — would often have dilapidated buildings in rundown Miami repainted and spruced up to suit his keen aesthetic sense.)

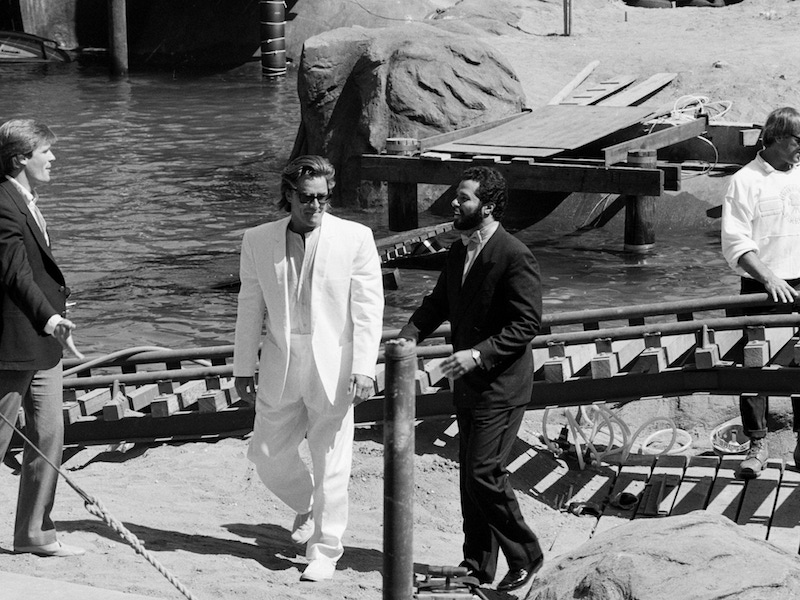

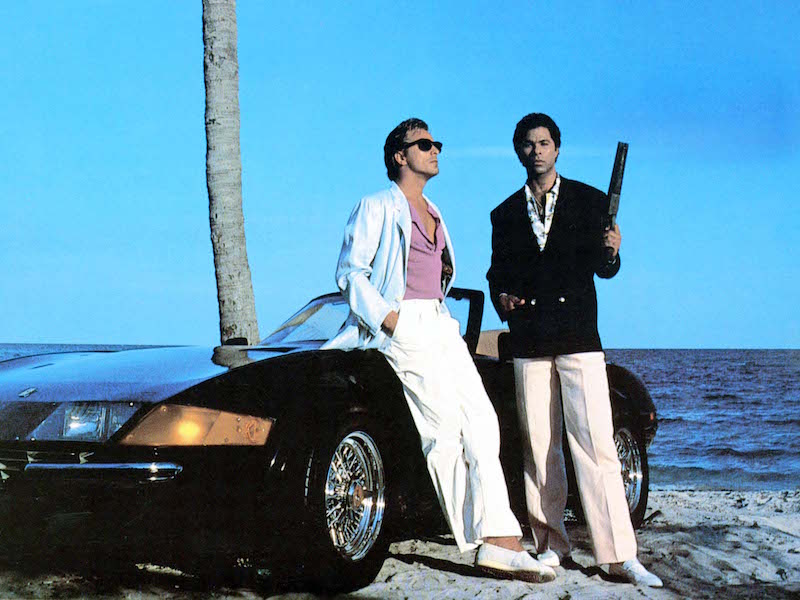

Not only did Miami grow to ape its glamourised, televised image, but the American man’s conception of cool, louche style came to closely resemble that of the show’s stars, Don Johnson (‘Sonny Crockett’) and Philip Michael Thomas (‘Ricardo Tubbs’). The duo would wear between five to eight outfits per episode, each the height of contemporary fashion — when asked how much was spent on clothing per episode, costume designer Bambi Breakstone replied, “We have a budget that we stay within. But it’s always too low.”

Though Tubbs’s east coast gangsta double-breasted tailoring had its fans, Johnson’s character’s look was particularly influential, sparking a much derided but enduringly appealing trend for white and pastel-toned linen suits from the likes of Hugo Boss, Nino Cerruti, Gianni Versace and Giorgio Armani, worn with t-shirts, espadrilles (no socks, natch), and jacket sleeves pushed up to expose an audacious yellow-gold Rolex. Crockett’s pioneering deployment of ‘designer stubble’, meanwhile, spurred countless men to shave sporadically or take up grooming accoutrements such as the ‘Miami Device’, a razor invented to keep facial hair at that ideal length. Tortoiseshell Ray-Ban Wayfarers experienced a sales boom thanks to Crockett’s patronage. And at the lowest common denominator end of the market, cut-price department store opened a Miami Vice-themed section in its menswear department, allowing those on a budget to copy the Crockett look for less.

There were no such pecuniary constraints for the show’s star characters, however. Miami Vice creator Anthony Yerkovich had initially formed the idea for the series after learning that law enforcement agencies were confiscating criminals’ property and using these trappings of wealth in undercover operations. His TV Vice officers would have access to an amazing array of luxurious lifestyle accessories, befitting the socio-economic status of a high-flying ‘cocaine cowboy’ (and way beyond the means of an everyday cop).

Again, Crockett got the better end of the deal, living on a 40-foot Endeavour yacht, making runs in a $130,000 Wellcraft Scarab 38 KV cigarette boat (sales increased by 20 percent thanks to this exposure), and — while partner Tubbs made do with a relatively frugal ’64 Caddy Coupe de Ville drop-top — tooling around town in an iconic black 1972 Daytona Spyder 365 GTS/4. The car was actually a replica built atop a Corvette chassis — unhappy with the show using a fugazi Ferrari, in 1986 the Italian marque agreed to supply authentic white Testarossas as a replacement. (Today, the model is immensely popular with 40-something collectors whose love affair with the Testarossa blossomed as boys, watching Crockett at its wheel on screen.)

Car makers, boat builders and fashion designers weren’t the only ones to benefit from ‘the Vice effect’. The producers spent a fortune licensing top-tier tunes for the show, turbo-charging sales of music by artists including Phil Collins, Glenn Frey, Chaka Khan, Dire Straits, Devo, Tina Turner, The Police and Roxy Music, immortalising Jan Hammer’s moody synth score, and spinning off three platinum soundtrack compilations, the first of which hit number one on the Billboard album chart.

A groundbreaker musically, aesthetically, stylistically, automotively, and a precursor for the spate of high-gloss cinema-quality television now on our screens, Miami Vice remodelled our sense of cool and helped turn America’s murder capital into one of its centres of chic — however vaguely gauche and roccoco.