Light Years: The Golden Age of the Night Club

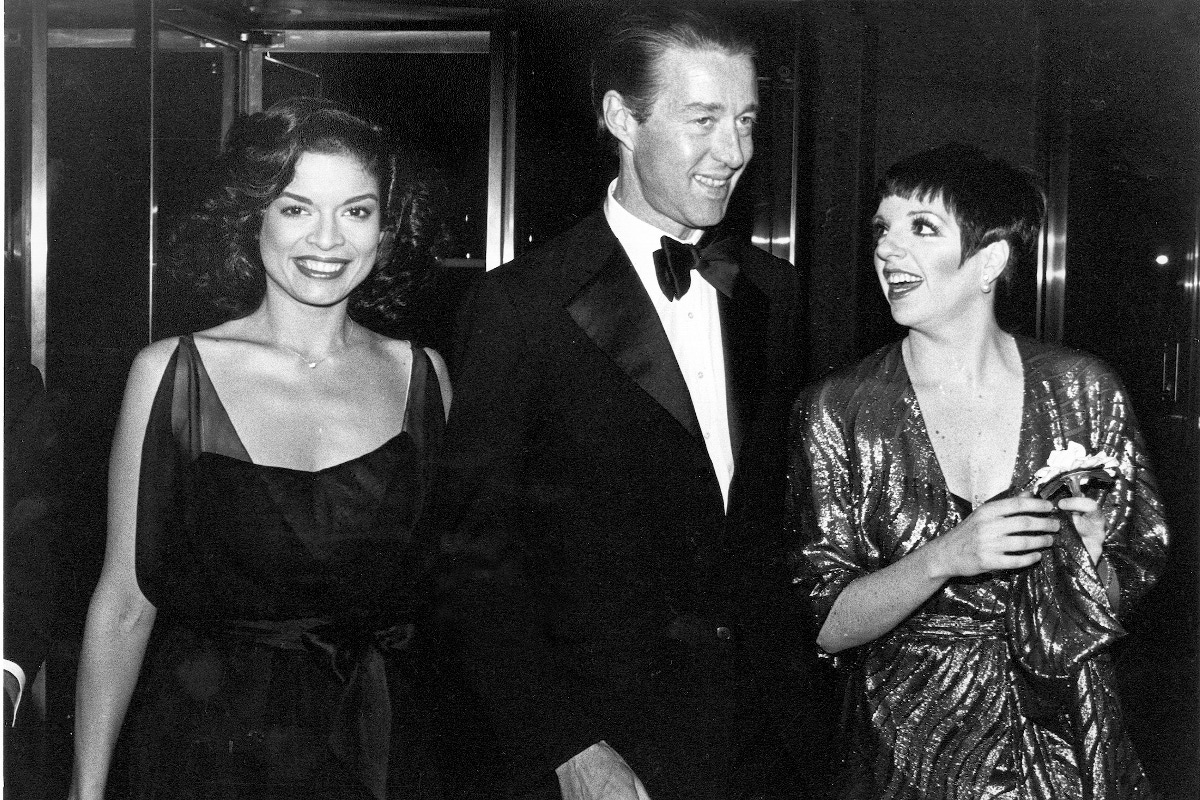

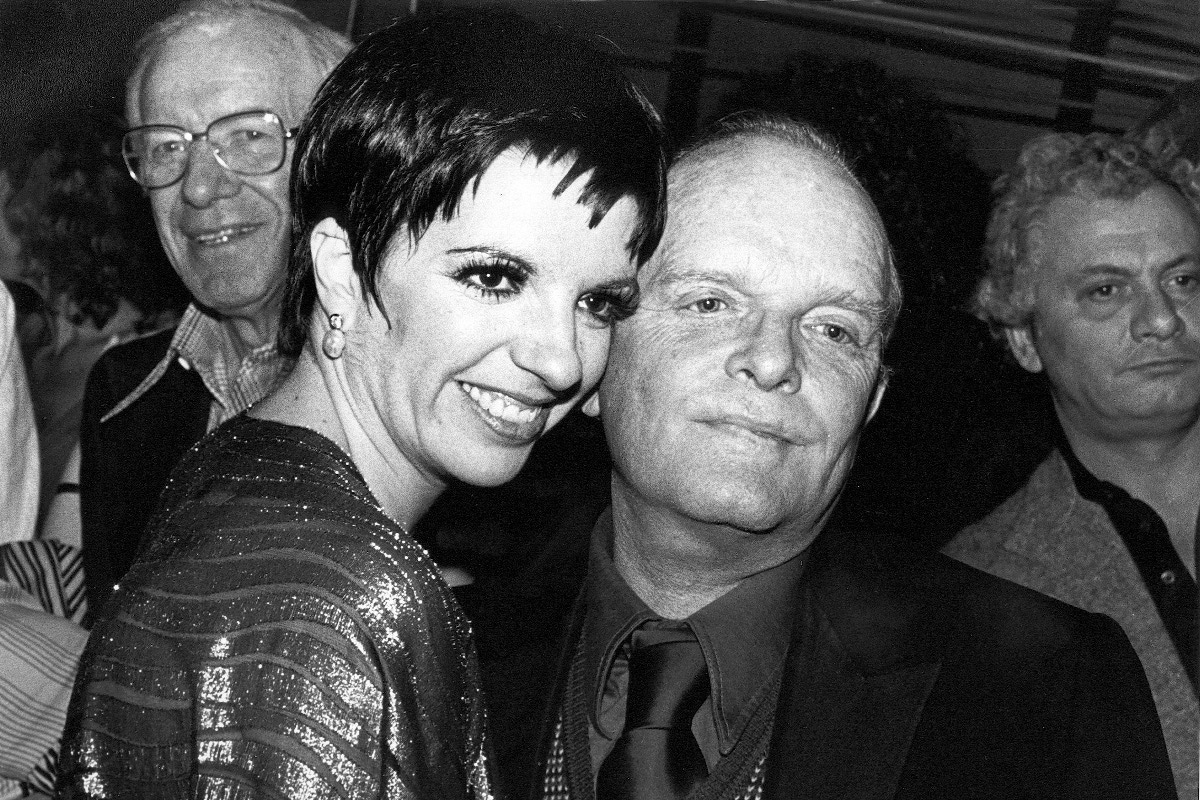

When you think of the seventies, what do you see? How about Bianca Jagger on a white horse at Studio 54, or Grace Jones on a pink Harley-Davidson at le Palace? Originally published in Issue 42 of The Rake, James Medd writes that whilst the seventies was the decade of economic and social unrest, it was also the golden age of the nightclub, when fashion, music and art came together to create a lifestyle so desirable it needed a strict door policy at all times.

As social historians begin to look back on the 20th century, the seventies are increasingly characterised as the era’s problem child. Recession, oil crises, the rise of mass consumerism, pollution, the self-help book, and progressive rock: it’s as if we’ve collectively bundled it all together and hidden it in a box in the attic marked Where It All Went Wrong. One area in which the seventies went very right, however, was in the nightclub.

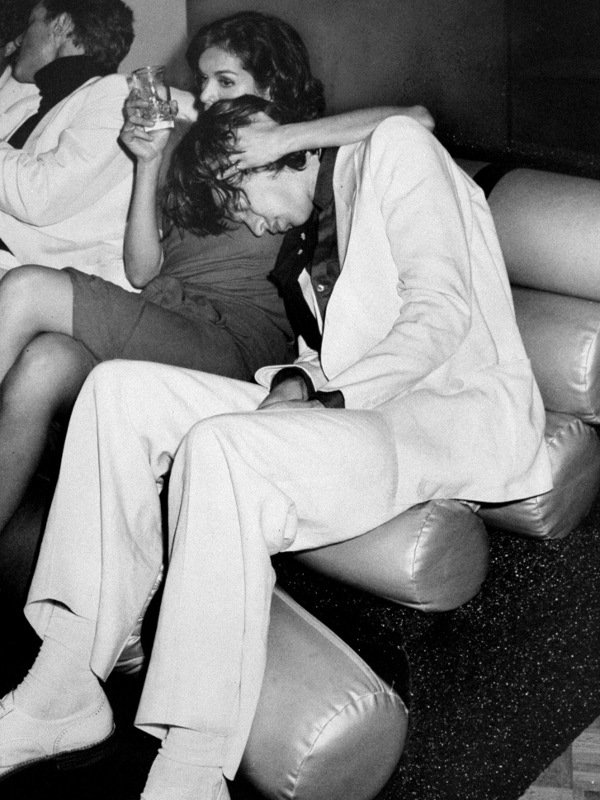

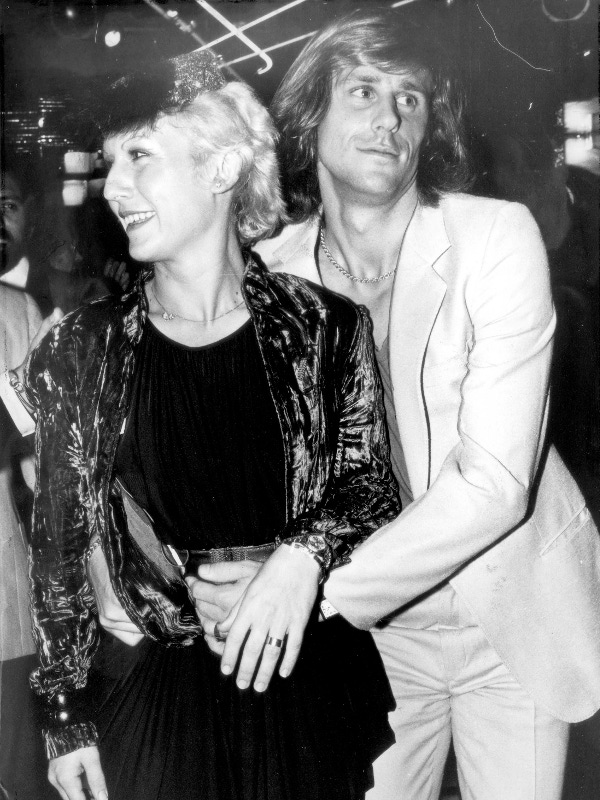

We’re not talking here about the drinking dens of thirties Soho, or about the Ministry of Sound or Haçienda in the nineties, but about the kind of place that would, quite happily, call itself a nightclub. This is somewhere where music would be played and where dancing would take place — where that might ostensibly be the main purpose of the place, though really where everyone has come to see and be seen (and possibly to do things they’d rather weren’t seen).

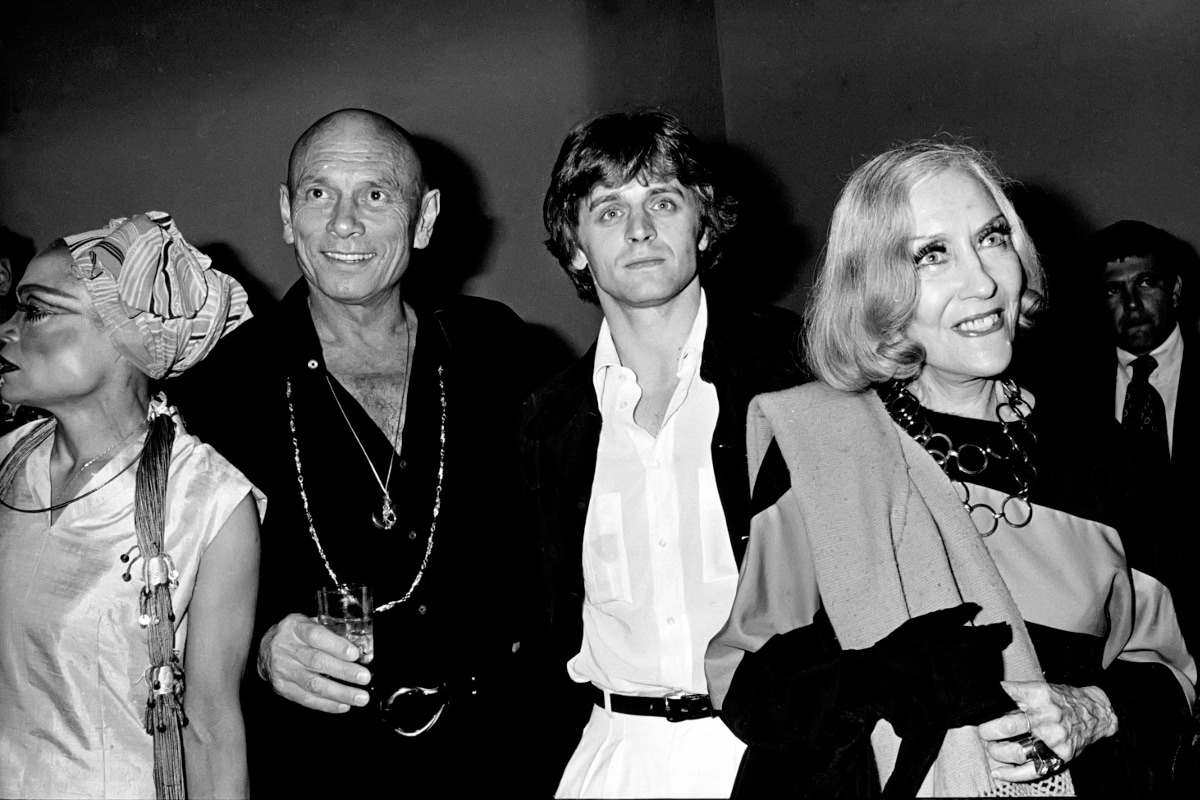

There are a few reasons why the seventies was the perfect time for such places to thrive. One of the most important was the move away from live performance to playing vinyl records. Once attention was no longer focused, at least theoretically, on the stage, it moved naturally to the clientele. And once that happened, the clientele very quickly began to make itself more interesting. Another reason was that, before camera-phones and social media, these characters could regulate their exposure to a paparazzi shot of entering or leaving; the rest of the night was their own business. This, allied with the third reason, of timing (the seventies came after the Pill, before A.I.D.S., and during cocaine, when the concept of vice briefly ceased to exist), made for a pretty good deal.

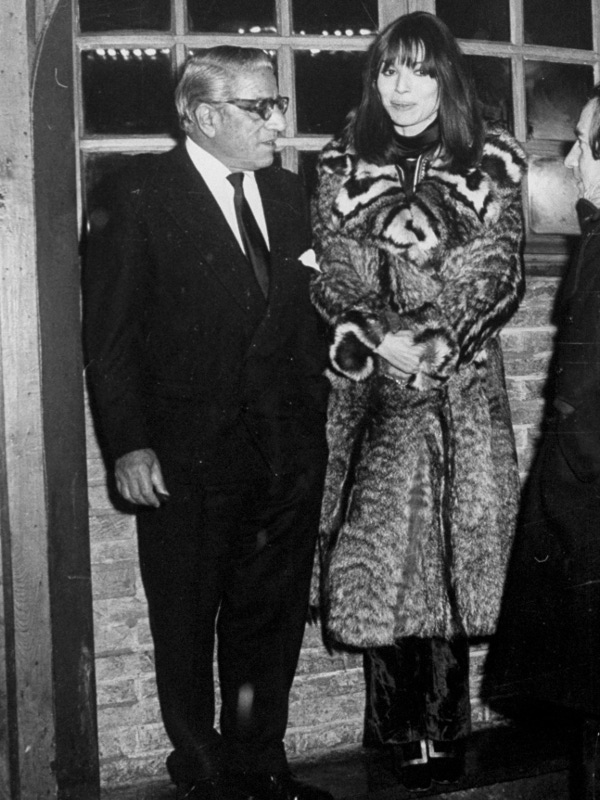

So who came up with this brilliant idea? Well, there’s a reason the full version of the word disco (‘le discothèque’) is French: it began in Paris. And, although we now know that nothing, from the wheel to Robin Thicke’s Blurred Lines, was ever invented by a single person, we’re going to hand this to Régine Zylberberg. A Belgian refugee born in 1929, she worked her way up from hat-check girl at the Whisky a Go Go to found the first discothèque, Chez Régine, in 1958, where she came up with the idea of using two record players in order to keep the music running without interruption. Known as the Queen of the Night (and not exclusively by herself), she hosted playboy Porfirio Rubirosa, the actors Alain Delon and Brigitte Bardot, and the singer Serge Gainsbourg. She also taught the Duke of Windsor how to dance The Twist, freshly imported from New York’s Peppermint Lounge.

For Karl Lagerfeld, “she quite simply invented nightclubbing”. Her only rival was Jean Castel, whose Chez Castel was adjudged by the Paris Snob guide of 1967 to be the most “sympathique” (friendly) of all the city’s nightclubs — although, it added, door selection was “sévère”. But while Castel remained in Paris, Régine expanded to Monaco, Monte Carlo and New York, rolling out her formula of intimacy, exclusivity and glamour. In New York, where the club was situated on the ground floor of the Delmonico Hotel on Park Avenue, Jack Nicholson, Diane von Furstenberg and Andy Warhol were regulars.

We’re not talking here about the drinking dens of thirties Soho, or about the Ministry of Sound or Haçienda in the nineties, but about the kind of place that would, quite happily, call itself a nightclub.The only place where Régine failed was London — twice, in fact — which she blamed on the British “lack of style”. And this despite stories that she mounted a complicated campaign of what would decades later be described as ‘hype’, forcing potential customers to queue around the block while staff pretended an empty club was full to bursting. (Supposedly, Princess Margaret requested admission and they were forced to set fire to the building to avoid letting her in.) Régine may have had a point about the Brits, but more likely it’s that she hadn’t factored in the essential element of class. Hence the success of London’s, and possibly the world’s, longest-running nightclub, Annabel’s. Named after the then wife of founder Mark Birley, this pinnacle of London nightlife is, on paper, so unpromising that it might be a very British joke: literally a converted coal cellar, it was decorated hugger-mugger in the style of an aristocrat’s bunk room, underlit and equipped with a dancefloor so small it would barely register as a stamp at the Post Office.

Its establishment came from a gang of aristos led by John Aspinall, who succeeded in opening a legal gambling club in Mayfair, at The Clermont. In 1963, Birley, one of their number, decided to dig out the basement so they’d have somewhere to drink. Like many of these places, its true attraction remains intangible: a lot to do with the host, something to do with the décor, more than a little to do with timing. As inveterate socialite Taki Theodoracopulos said: “If it weren’t for Mark Birley, I probably wouldn’t have stayed in London for as long as I did. London was a grubby place. In those days you built your life around going to Annabel’s.”

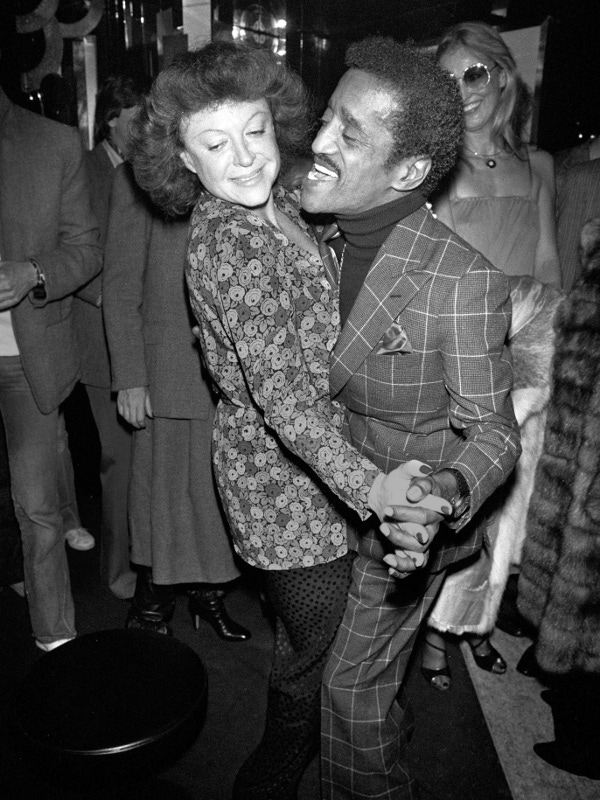

Like Régine’s, Annabel’s attracted names as stellar as Frank Sinatra and Jacqueline Onassis, as well as the occasional president or queen, but it was the quality of its regulars that kept it at the top of the game for so long. In the swift-moving, socially mobile world of the sixties, clubs such as The Scotch of St. James, The Ad Lib or The Speakeasy would grab the limelight and then fade almost as fast, but Annabel’s carried on regardless, always rather above fashion. Its only real rival as the seventies wore on was Tramp on Jermyn Street, where visiting stars from Hollywood might mingle with Joan or Jackie Collins, even Mick Jagger or Michael Caine, but, as with Régine, it was not in the same class.

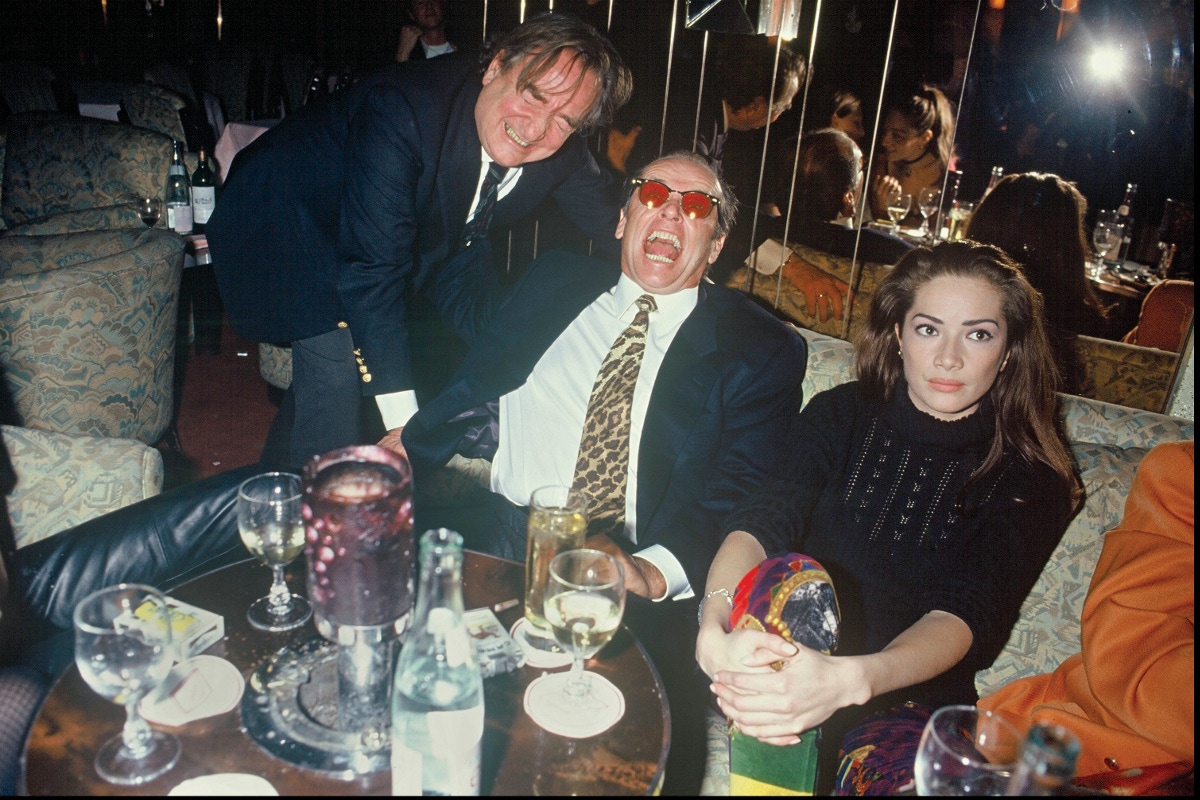

In winter, much of the crowd found at Annabel’s or Régine’s decamped to Gstaad, where from 1971 they found a nocturnal home from home at The GreenGo, situated in the basement of the Palace Hotel. Its seasonal influx of European and Hollywood royalty spent the après-ski hours dancing to disco hits on a dancefloor suspended over a basement swimming pool, into which the graduates of the exclusive Le Rosey finishing school still hurl themselves on the closing weekend of the winter term.

To its credit, The GreenGo has barely changed since the days that Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor clinked glasses at the bar with King Juan Carlos or Prince Rainier, all reflecting surfaces and what it boldly chooses to describe as the influence of Paco Rabanne. Much the same could be said for its summer equivalent, Les Caves du Roy at the Hôtel Byblos in Saint-Tropez, where a warren of V.I.P. booths cater for a clientele to whom the music is little more than a distraction from the serious business of seeing and being seen.

Which, of course, is as it should be. Music has never been the point of any nightclub worthy of the name. The great nightclubs of the era brought together the worlds of fashion, cinema, music and art in a way that not only excited those involved but also thrilled everyone else — those who felt they might be able to join in. Consequently, behind every great club lay a fierce, or more likely ferocious, door policy. For the already fabulous, a proper nightclub provided closed-shop safety — no paparazzi, no journalists writing up last night’s misbehaviour, and consequently a licence to frolic. But for the ordinary or the aspiring, it created an irresistible attraction: the chance to walk among the chosen few, to be made special.

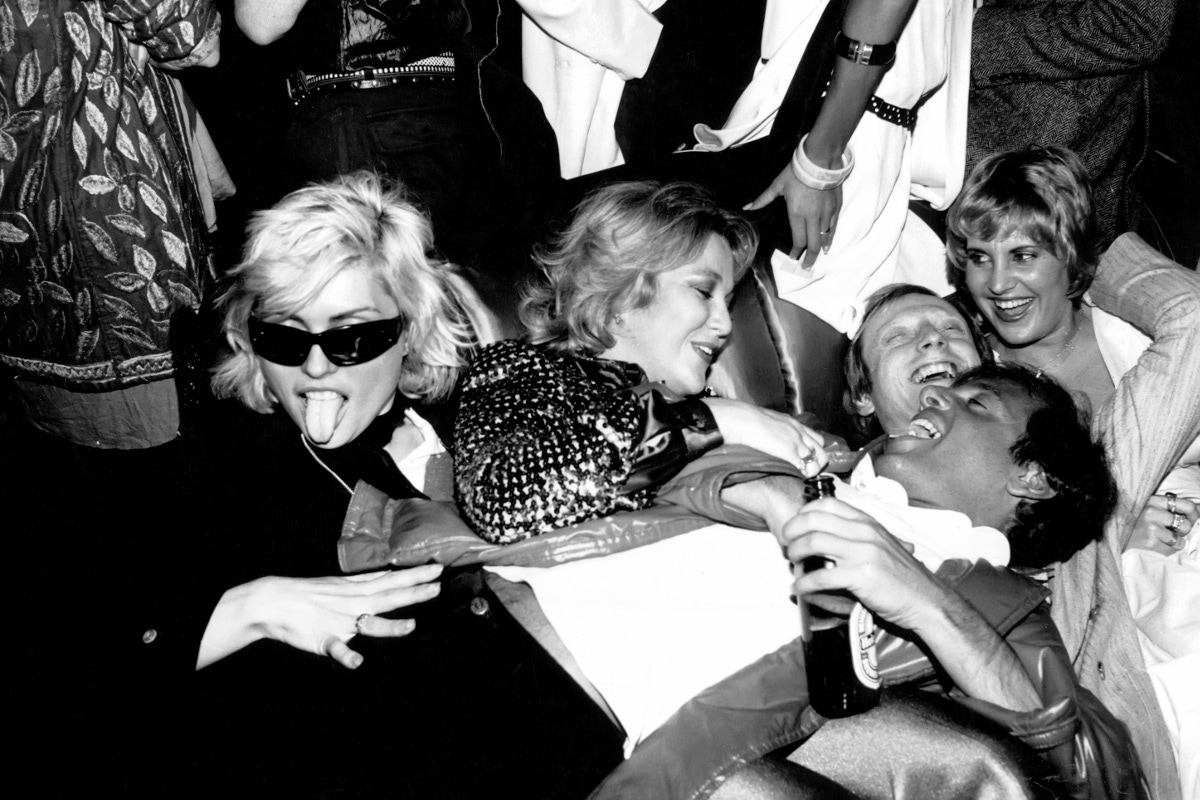

Nowhere worked this angle better than Studio 54, New York’s short-lived but bright-burning disco inferno. In the 33 months it was open, from April 1977 to February 1980, this concrete barn set in a former television studio managed to eclipse any other nightclub in history. Taxiing in on the rise of gay nightlife in the city, it took off with the forceful ambition of its founders, Ian Schrager and Steve Rubell, the unbeatable connections of Peruvian publicist Carmen d’Alessio, and an infinite appetite for showboating that saw themed parties for Dolly Parton involving hay bales and sheep, and the legendary night when Bianca Jagger rode across the dancefloor on a white horse.

Constant invention and reinvention kept the club in the news, but it was the door policy that made Studio 54 the most sought-after night out in the world. Rubell would stand on a stool outside the door, handpicking those that made the grade. He compared it to mixing a salad or casting a play. The son of a Brooklyn postal worker, he admitted, “If I wasn’t the owner, I wouldn’t be allowed in”. Among those he turned away were Frank Sinatra and John F. Kennedy Jr, not to mention Nile Rodgers and Bernard Edwards, then providing some of the club’s favourite tracks as Chic. Those who made it inside might find anyone from Warhol (“the Good Housekeeping seal of approval” for any club, according to Schrager) to Mikhail Baryshnikov, Diana Ross to Debbie Harry, Nicholson to Omar Sharif, Truman Capote to hippy guru Dr. Timothy Leary. It was the concept of celebrity taken, for the first time, beyond any logical conclusion, to a place that was, for those included, very heaven.

Behind the scenes there was, perhaps inevitably, another world — of sex, chronic drug use, and, fatally, financial corruption that saw both Rubell and Schrager imprisoned for tax evasion. Rubell’s boast that “only the Mafia were making more money” underlines the fact that Studio 54 was always a commercial, rather than artistic, venture. The music made it the most mainstream disco, much as at Annabel’s, where, as the reliable social commentator Peter York pointed out, the diminutive dancefloor has always been “mostly occupied by people who don’t like music and can’t dance”. After Studio 54’s decline, its clientele made their way to more radical clubs, such as the Mudd Club, where a similar mix of artists, literati and socialites found themselves assailed by a stew of post-punk Latin beats, rock ‘n’ roll, and Afro-funk. Few survived the experience.

Before this, back in late-seventies Paris, Régine was now a figure of history, but a similar game was afoot in an old bathhouse in the third arrondissement. Les Bains Douches, decorated by a young Philippe Starck and DJ’d by a very young David Guetta, gathered the city’s avant-garde alongside visiting icons such as Prince, Jean-Michel Basquiat and Robert De Niro. Les Bains had a swimming pool by the dancefloor and a city enjoying a period of financial extravagance, but vitally, it also had Marie-Line, a line-picker of world-class stature who was known for two mottos: “Rich or poor, young or old, famous or unknown, but no one ordinary”, and the rather more brutal, “I don’t think that’s going to be possible”.

It also had a rival, Le Palace, in the 9th, where a similar blend of fashion, music and film types were gathering, such that Paris’s most-in-demand sometimes had to choose where their loyalties lay. What Fabrice Emaer, impresario of le Palace, had over Les Bains was the backing of the philosophers: his idea may have been to rival Studio 54, but for the great semiotician Roland Barthes, what he created was “the excitement of the Modern, the exploration of new visual sensations due to new technologies ... a place that is sufficient unto itself”. If this seems an overreaction, you were probably not there for the opening night on March 1, 1978, when Grace Jones sang La Vie en Rose atop a rose-strewn pink Harley-Davidson.

Such glory could not last. Like Kubla Khan’s Xanadu, the nightclubs of the golden age fell into decline, were taken over by lesser rulers, and faded to dust. By the late eighties, with the rise of house music, nightclubs split into the ‘club’, where dancing became the total focus, and a new breed of meeting houses based on the old 19th-century gentlemen’s club. In the decades since, most of the great nightclubs have been revived in some form or other, always with disappointing results. Many, many more have been created in their image, given faux-exotic themes or false grandeur, and an illusion of elitism that is paper-thin. If anyone can get in, there is no nightclub, only an over-priced wine bar. For the nightclub, the golden age is gone and no amount of gilding can bring it back.

The article originally appeared in Issue 42 of The Rake.