The Most Decadent Decades of Dinner Dress

Slipping Standards

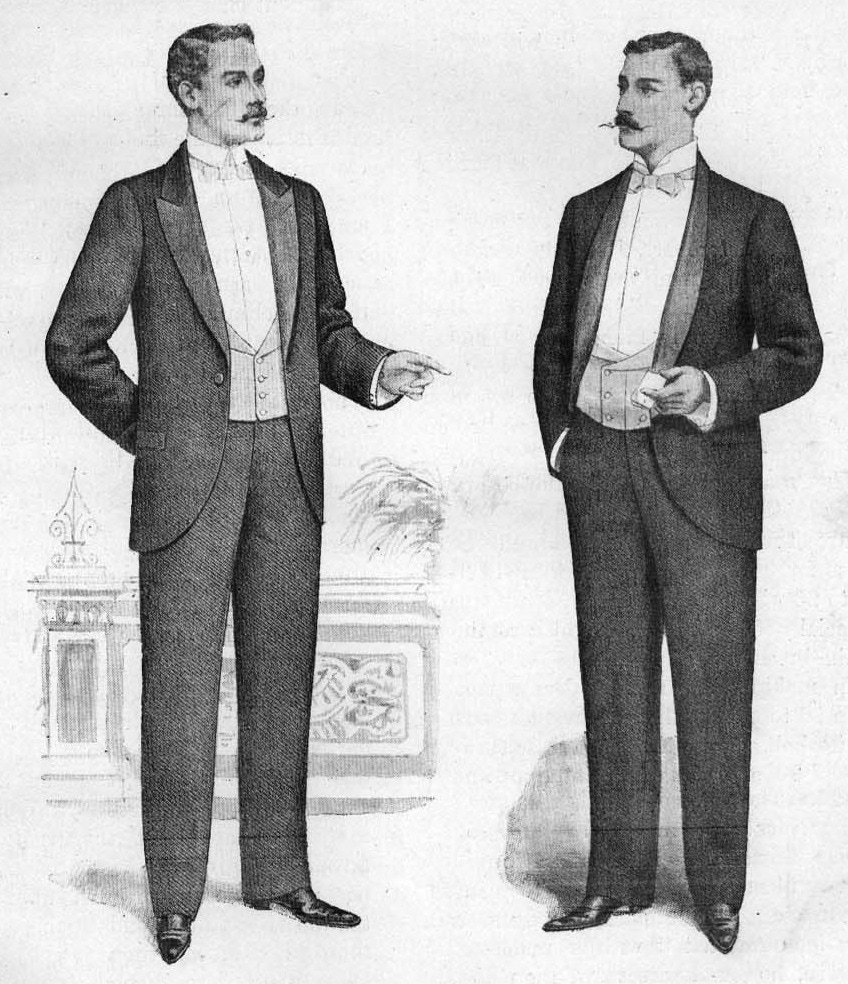

The contentious origins of black tie are of course well known; a great debate rages between the stalwarts of Savile Row and American high society as to whether it was a New York socialite or a former British monarch that invented the dress code. Perhaps the most diplomatic answer is that it was a combination of both. On the English side of be fence, the story goes that in 1865 His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales (soon to be Edward VII) had an informal ‘celestial blue’ evening coat cut for relaxed dinners at Balmoral, so say the order ledgers of the Prince’s tailor, Henry Poole at any rate. The coat was intended to be a hybrid between formal evening tails and smoking jacket, which removed the need for His Royal Highness to change after dinner. Cut as a short ventless jacket, lacking in the tails of a frock coat for comfort, yet retaining formal faced lapels and buttons, the Edwardian predecessor of the dinner suit was born. It was moreover, an invention born of supreme laziness and whimsy; a thoroughly unconventional and arguably improper garment, created and worn with reckless abandon by the renegade prince. Had it not been for His Royal Highnesses’ magisterial blood, the chances of the dress code taking off would most likely have been minimal. Not a bad pedigree for a garment that was to become synonymous with excess and revelry in years to come. In 1886, some years after the Prince’s maverick sartorial brainwave, one Mr James Brown Potter, a wealthy American aesthete and member of New York's legendary Tuxedo Club, met with the Prince of Wales and was subsequently invited to dine at Sandringham. The two shared Henry Poole as their tailor and at a loss as to what to wear, Potter consulted Mr Poole for some style advice. He replied confidently, that a short, midnight blue evening coat was just the thing. Unsurprisingly, it went down a storm at the royal residence, so much so that Potter took to wearing his new coat out to dinner at the Tuxedo Club. It was embraced by the club’s members with almost reckless abandon and soon New York society at large was embracing it as the fashionable thing to wear to wild parties; this being a trend which was to continue well into the twentieth century.Puttin On The Ritz

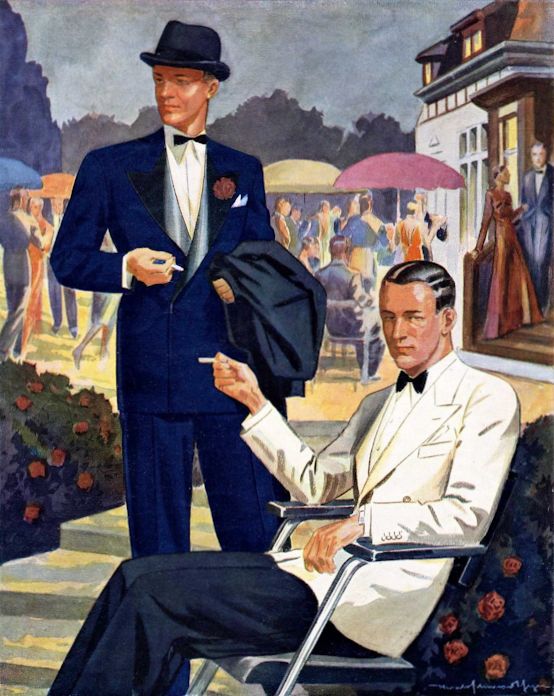

Having been jettisoned into the public glare by the combined reach of New York's high society and a rather improper Prince, it wasn’t long before the bright young things of the Jazz Age, both in Europe and America, had caught the dinner dress bug. Fashion plates and catalogues dating to the early 1920s demonstrate a steadily growing demand for contemporary dinner dress, as the social optimism, increased freedom and inevitable excesses of the period popularised an increasingly less formal mode of socialising. Even so, the dinner suit was considered subversively informal for much of the period, with the establishment scoffing in shock in their White Tie and tails whenever a penguin suit entered the room. Ten years on, the 1930s were at once a little more relaxed, but also more divisive thanks to the extraordinary fallout of the great depression. It was a decade of continued excess and bravura on the part of the wealthy, who continued to laud it at the top of the social tree in their utterly gauche ‘after-six’ wardrobes. In 1935 a writer for the New York Herald Tribune calculated that a “well-attired” New York gentleman’s evening dress could be worth as much as $4,975 including additional furnishings like his evening coat, cufflinks, scarf and gloves – a frightful sum, easily enough to afford a sports car at the time. As such, the dinner suit lost much of it subtlety, becoming a brash and aggressive social statement. The peak lapel was in (the bigger the better) as was the roped shoulder, full-cut pleated trouser and loud evening waistcoats. It was an ostentatious and far from tasteful expression of power and prestige, which goes some way to explaining why one associates the dinner suit of the 1930s primarily with gangsters, as evinced by modern televisual hits like Boardwalk Empire. Even the rather pessimistic seminal novels of the time, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby for example, place black tie firmly in the court of the dissolute and decadent criminal classes.Golden Oldies

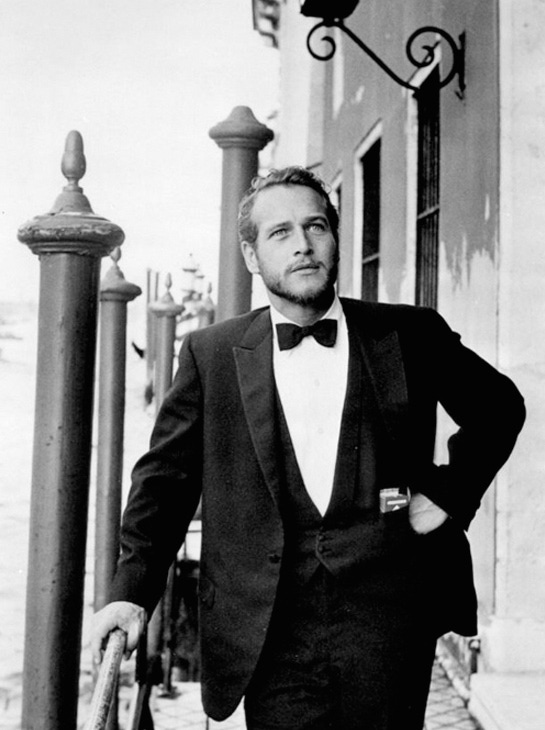

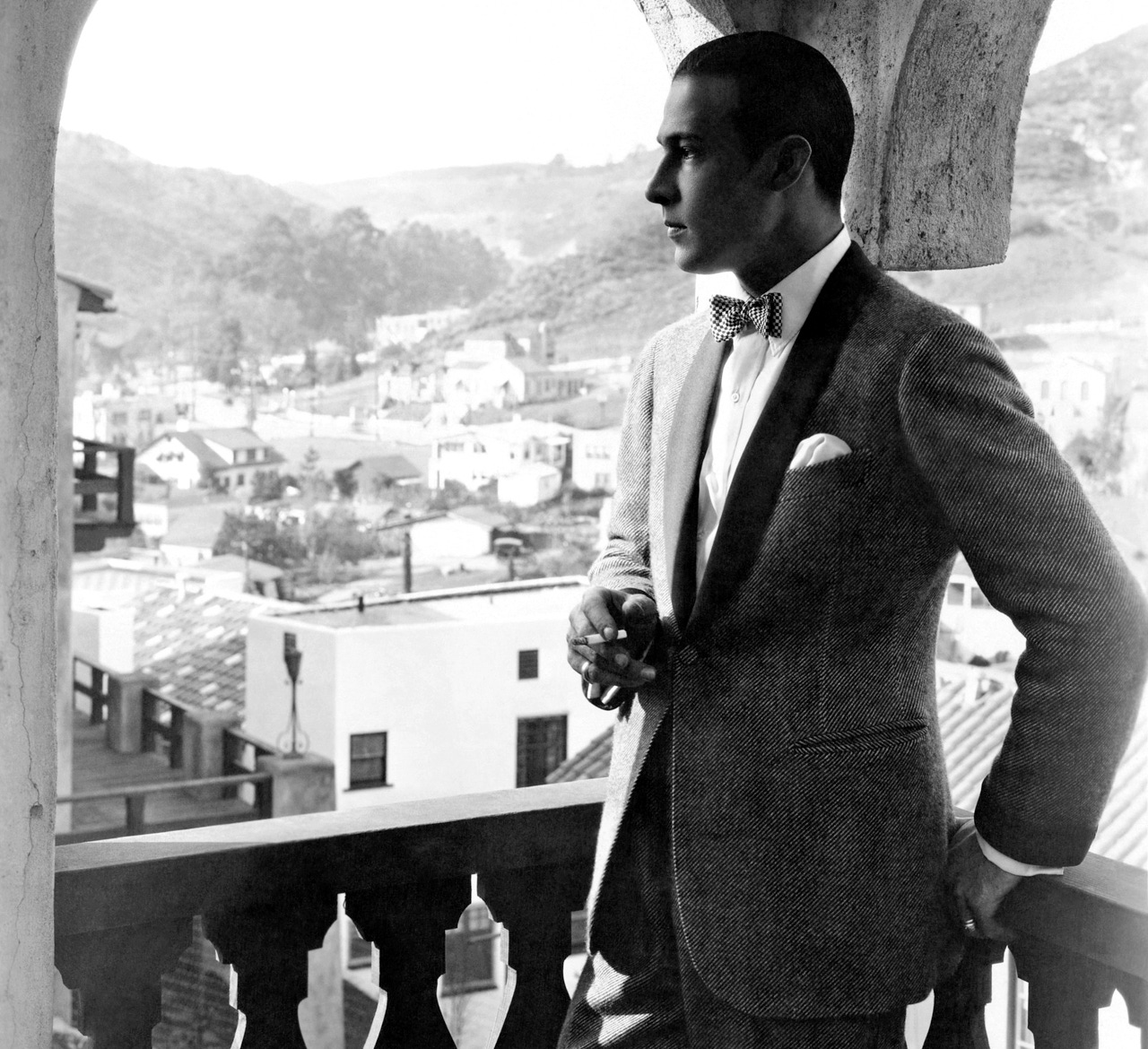

Even so, this rather unsavoury association drew a good deal of attention, and moreover was just what Hollywood needed to fire the public’s imagination. Within a few years, bestride the shoulders of stars like Cary Grant, Clarke Gable and Gary Cooper, the dinner suit was reborn the very pinnacle of heart-throbbing, masculine elegance. The ‘golden age’ of Hollywood presents its stars with an unashamedly masculine aesthetic, subtly sexy in it’s own way; with rugged, strong jawed men sporting suits with statement-making architectural shoulders and generous, full-cut chests. As popular culture, rather than the social elite began to influence what the man in the street wore, cinematic icons like Bogart’s shady Rick in Casablanca also popularised the doubled-breasted dinner suit, which particularly in its generous low-buttoning variety, is considerably more louche than the formal, pumped-up three-piece suits common to the glitterati of the 1930s. By the mid-40s, soft spread collar shirts, often with covered plackets and pleats also lent the dress code a slightly softer, more nonchalant aesthetic.

Tuxedo Junction

Following ten years of thoroughly drab experimentations with dinner dress in the 50s, including the ghastly creation that was the ‘Burma shade’ dinner jacket, hope was to be renewed come 1960. Mod culture and its slim, trim, youthful silhouette ushered in a radically different era of razor sharp contemporary evening suits, giving birth to the notion of the 'cocktail suit' as it's understood today. Though of course, the vast majority of men remained comfortable in a conventional black tuxedo, a wealth of space age options also entered the sartorial arena, reflecting wider political and technological change, as well as increased social optimism. Think ballsy shantung jackets, garish geometric woven jacquards and new synthetic prints (for example Rayon and Tonik jackets worn with equally garish coloured bow ties and cummerbunds) perfect for not being mistaken for a waiter in the hotel bar on your ultra-modern Caribbean cruise.

(Somewhat) Smooth Maneuvers

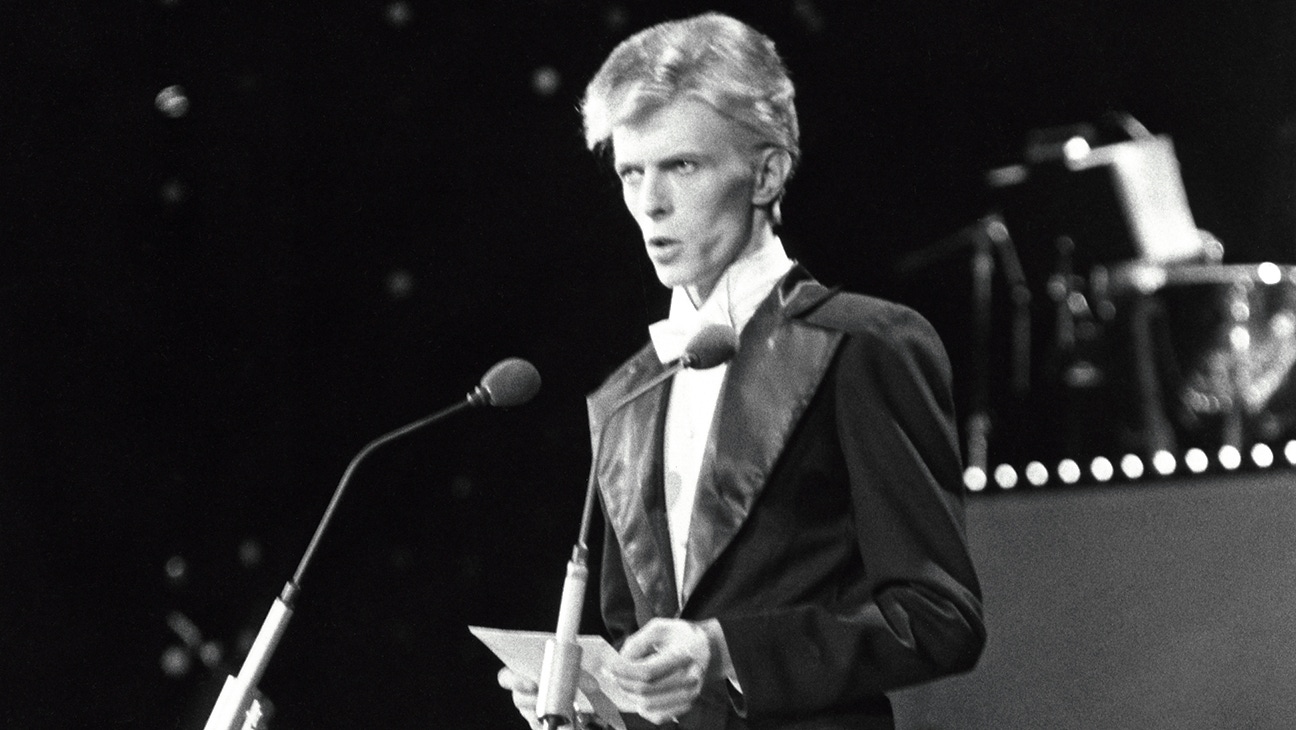

Thinking about the suit of the of 1970s inevitably conjures up the archetype of the rather uncouth party animal, gyrating around the dance floor with a bottle of Cinzano, flapping his grosgrain-trimmed trouser flares with frilly fronted evening shirt adrift. Fortunately, the reality of '70s formalwear is a little more sophisticated. Indeed, those of an elegant persuasion enjoyed a revival of relatively restrained, sophisticated evening dress – with the classic dinner suit returning to form as a masculine success symbol, albeit with pumped up proportions and the indomitable flared leg. Louche cream dinner jackets came back with a bang, thanks in no small measure to Hollywood’s renewed fascination for Ivy League style. Come the middle of the decade, the world’s dream-selling sartorial powerhouses (most notably Ralph Lauren, Armani and Valentino) were making a point of designing eveningwear that captured this thoroughly aristocratic, luxuriant aesthetic, redefining the sensuality of the dinner suit in the process. The Paul Newmans, Steve McQueens and Robert Redfords of the time made for an impossibly sexy prospect both on and off the silver screen and this was a look that menswear designers were only too happy to channel in their own work. In Europe, taking the dinner suit to even more aspirational heights were of course those iconic musicians and pop stars who offered an escape from the muddy brown reality of economic slowdown; performers like Bryan Ferry, headlining Roxy Music and David Bowie’s ‘The Thin White Duke’ dressed in a variety of outré, yet nostalgic dinner suits both on and off stage – appealing unashamedly to a lost sense of glamour and sophistication. Films of the time do much the same; The Godfather and The Sting for example. In the decade that gave rise to the notion of the hairy man’s man with his ‘keys in the bowl’, this nostalgic, smouldering aesthetic was just what a performer needed to capture a slightly more refined sense of sex appeal.Brave New World

With dinner suits suffering from a relatively quiet spell since, we’re thrilled to say that men have taken to experimenting with dinner dress once again. What is more, the conventional framework of black tie is in flux for the first time in its history. As our cosmopolitan, international society continues to evolve, formal dress codes are devolving and eveningwear is no exception. More so than ever before, gentlemen of taste are playing with the genre; embracing decadent silk jacquards, iridescent mohair cocktail suits, coloured voile or denim dress shirts, velvet smoking or lounge coats and different cuts of jacket and trouser. These experimentations are gathering pace in the world of designer menswear and one can't help but sense that a new period of confident, expressive evening dress is dawning; one need only look at the catwalks of London Collections Men and Paris Fashion Week for evidence, or else towards society events like The Oliviers for irrefutable proof. This is something that The Rake salutes whole heartedly, so allow us during the next instalment of this series to induct you into our rules for mastering a contemporary black tie dress code. We promise you, by the time we're done; you'll never look at a staid black dinner suit in the same way again. More on that to come next week.