The Fake's Progress

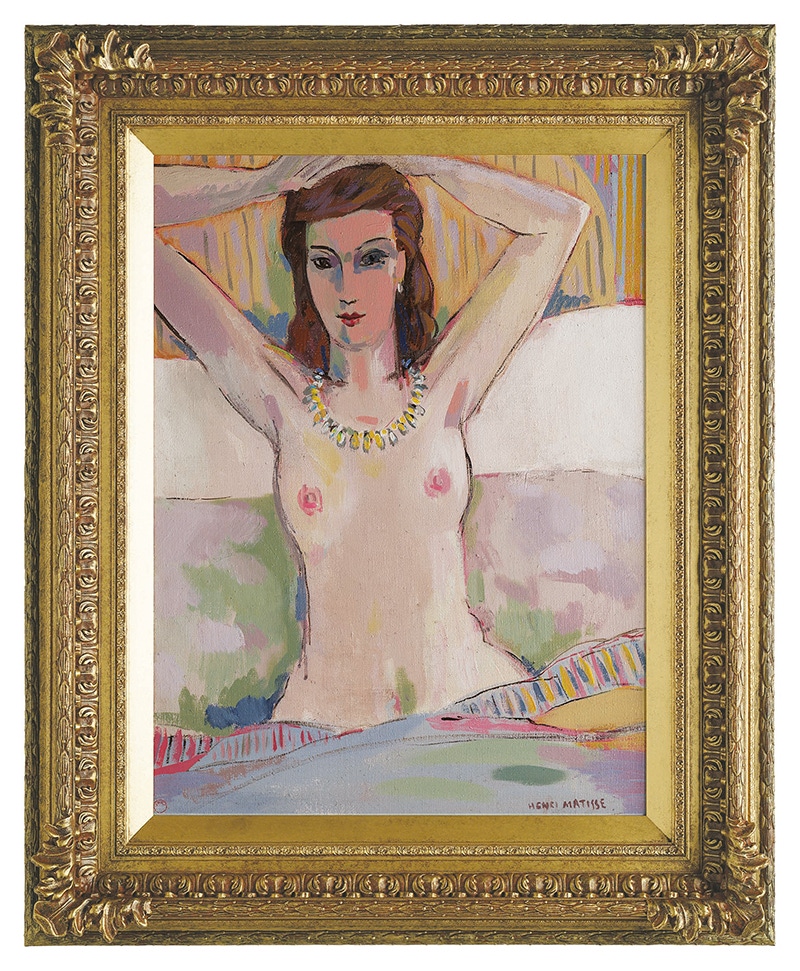

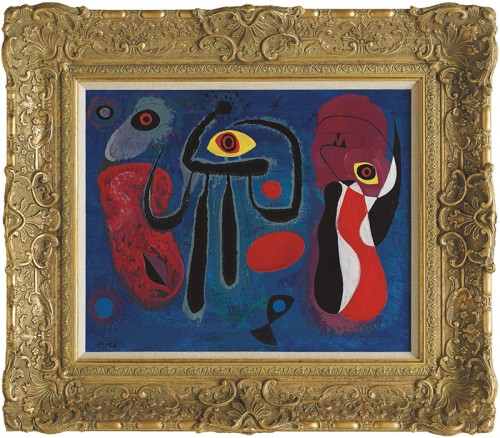

John Myatt is showing a visitor around his studio. 'I've got a Cazanne on the go,' he says, indicating his easel, where a familiarly blocky, colour-drenched, proto-Cubist Provence landscape is in progress. 'Here's a Monet,' he continues, pulling back a few stacked canvases to reveal a fog-burnished view of the Houses of Parliament and the Thames, immediately recognisable to any student of Impressionism. An Analytic Cubist 'Picasso' - fragments of playing cards, pipes, newspapers and musical instruments all present and correct - sits on a shelf above a couple of 'Joan Mirós' from the Catalan Surrealist's jubilantly splotchy Constellations phase. 'I'm particularly proud of that Matisse,' adds Myatt, pointing to a drawing of a smiling woman conjured in a few sweeping, exuberant lines, characteristic of the French master. 'And, this is one of my favourite van Goghs,' he concludes, as we return to the dining room of his farmhouse, where an expansive, vivid landscape, typical of the Dutch legend's almost-hallucinatory renderings of the fields around Arles, dominates the wall.

We haven't stumbled across a treasure trove of previously undocumented modernist masterpieces in this obscure corner of midland Britain, a couple of hours north of London; Myatt produced all of the paintings himself. They are forgeries - or, as he calls them, 'genuine fakes', 'signed' by the artist in question on the front, but by Myatt on the back. His classification may sound like an oxymoron, but Myatt is at pains to distinguish his work: 'If I were doing forgeries, I'd have to find paint from 1910, and use period canvases, stretchers and frames,' he says. 'I actually use a blend of acrylic and house paint, mixed with K-Y Jelly. All I've ever sought to do is amuse myself, and create something that deceives the eye. And I don't do copies. There are millions of painters who could knock you up a Mona Lisa, but I prefer to produce something in the style of Leonardo, a painting or drawing he never quite got round to doing.' Myatt's bearing is naturally modest, but here he allows himself a wry grin. 'That's the difference.'

Myatt's facility with the brush - he compares his skill at appropriation to 'trying out different styles of handwriting' - has brought him some renown and some notoriety. He first advertised his services as a genuine-faker with a small ad in the personal pages of satirical magazine Private Eye ('from £200'), but between 1986 and 1994, he upped the ante, working with a master scammer named John Drewe (who had, at various times, claimed to be a physicist and a Ministry of Defence advisor, and who was an early client of Myatt's) to auction off 200 paintings 'by' the likes of Giacometti, Gleizes and Nicolas de Staël. Drewe supplied fake certificates of authentication and paper-trail provenance, and experts gamely endorsed the pictures despite the decidedly late-20th-century materials involved in their fabrication; the auction houses sold them on (there is an invoice from Christie's for the sale of two of Myatt's 'Ben Nicholsons' framed in his downstairs toilet), and Myatt estimates that he made around £275,000 from the racket.

The pair were eventually rumbled by a Giacometti scholar, taken aback by a somewhat ham-fisted portrait in a Christie's catalogue ('Not one of my best,' Myatt concedes), and Myatt was sentenced to a year in prison (he was released after four months for good behaviour; Drewe, regarded as the mastermind by Scotland Yard, was given six years). Upon his release, Myatt vowed never to paint again, but a detective involved in his case asked him to create a family portrait for him. He eventually went on to front a Sky Arts television programme called Fame in the Frame, in which he painted celebrity sitters' faces into works from the art-historical canon - comedian Frank Skinner into a replica of van Gogh's 1888 Self-Portrait with Felt Hat, television presenter Paul O'Grady into Grant Wood's American Gothic, and so on.

'There's been a vast amount of interest in the criminal part of what I've done,' says Myatt now, sipping at a cup of coffee. 'It glamorises things somehow, and the public perception is that [forgers have] got one over on a snooty and unpleasant art establishment. Not that that was ever my intention,' he adds quickly. 'I just fell into it. I mean, the whole history of art revolves around artists lifting the styles of other artists. What was it Picasso said? 'Good artists copy, great artists steal.''

To see just how comprehensively some of the 20th century's most eminent forgers have taken Picasso at his word, an exhibition currently touring American museums is instructive. 'Intent to Deceive: Fakes and Forgeries in the Art World' highlights five figures, placing their work alongside those of the artists who 'inspired' them, and, according to the exhibition's curator (and art-fraud investigator), Colette Loll, 'exposing their infamous legacies and analysing how their talent, charm and audacity beguiled the art world'. Myatt is represented by a 'Monet', a 'Vermeer' (Girl with a Pearl Earring), a 'Matisse' and a couple of 'Raoul Dufys'. Alongside him is Han van Meegeren, the Dutch forger who churned out 'Vermeers' of Biblical scenes in the 1930s, one of which - The Supper at Emmaus - was hailed by authoritative Vermeer expert Abraham Bredius, former director of the Mauritshuis museum at The Hague: '[The work is] a - I am tempted to say the - masterpiece of Johannes Vermeer of Delft.' This piece was bought by the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam for 520,000 guilders (about USD6.4 million today), and another - Christ and the Adulteress - was sold to Hitler's deputy, Hermann Göring, for 1.6 million guilders, and was captured with him as he fled to the Austrian border.

There is also Elmyr de Hory, an eccentric figure whose very identity is opaque (he claimed to be a Hungarian aristocrat and affected a golden monocle). De Hory sold the vast majority of his prodigious output, via his dealers and co-conspirators, to US oil tycoon Algur Hurtle Meadows in the '60s; at one point, the latter's inventory included over 15 'Dufys', eight 'André Derains', seven 'Modiglianis', five 'de Vlamincks', three 'Matisses', two 'Bonnards', and single examples of 'Gauguin', 'Degas', 'Laurencin', 'Picasso' and 'Chagall'. In Orson Welles's quasi-documentary F for Fake, de Hory - the subject of the film - shows one of his 'Modiglianis' (for which he felt 'a particular affinity') as well as a 'Matisse' drawing: 'his lines,' sniffed de Hory, 'were never as sure as mine'.

Then there is Eric Hebborn, who produced over 1,000 drawings in the name of various old and newer masters, from Mantegna and Rubens to Hockney and Augustus John ('I improved his oeuvre,' he said of the latter. 'My drawings are more popular than his.'). And making up the quintet is Mark Landis, a diagnosed schizophrenic who donated a large number of forged paintings and drawings - of Paul Signac and Honoré Daumier, among others - to a variety of American institutions while assuming various identities, including that of a Jesuit priest.

In the aforementioned touring exhibition on forgery, the show includes various personal items alongside the pictures - Myatt's splattered green painting smock, Landis's priest collar, de Hory's palette - but curator Colette Loll does not want visitors confusing them with holy relics. 'I didn't want to glorify these men as cultural folk heroes, which the media tends to do,' she says. 'My passion is to expose forgery as a crime against cultural heritage, and to re-educate people on the legal, moral and financial implications - how artists' canons and experts' reputations are undermined and traduced.' The problem, she continues, is that because the show opened in Massachusetts, audience reactions to the visual sleights of hand have erred on the side of delight rather than indignation. 'It's like a really great conjuring trick or a brilliant verbal impression of someone,' she says. 'People have been looking at the de Hory 'Picasso' and the real thing, side by side, and they love being taken in. They also love the fact that the art market, which is not self-policing or transparent, was taken for a ride by these guys.'

By proposing an alternative fakers' canon, the show also brings the knotty question of the value of the most famous authenticated fakes into sharper focus. 'No authentic modern masterpiece is as provocative as a great forgery,' wrote the artist and critic Jonathon Keats in his book Forged: Why Fakes are the Great Art of Our Age. '[Forgers have] upset commonplace assumptions about culture and authenticity, belief and identity.' Loll herself describes the best-known examples as 'important cultural artefacts', and notes that van Meegeren's The Head of Christ (bought by the Boijmans in 1941 as another 'unearthed Vermeer' for 475,000 guilders, or approximately USD4.4 million today) arrived from Rotterdam with the same security arrangements - escorts, conservators - as any authentic masterpiece would have required.

Yet another van Meegeren 'Vermeer'-Christ and the Scribes in the Temple-sold for nearly USD40,000 at a Christie's auction in 1996, while any de Hory 'Modigliani' that goes into the market is likely to fetch the same price. That's partly due to the whiff of scandal that surrounds counterfeits in general and their names in particular. Van Meegeren was a failed painter of insipid genre scenes, whose disdain for modern art (he reckoned van Gogh's 'finger painting' was part of the 'spiritual sickness' that was corrupting the Netherlands) fed into the Nazis' championing of kitsch völkisch Aryan propaganda imagery. His supply of biblical 'Vermeers' (actually painted with the newly discovered liquid Bakelite and 'aged' in an oven for a couple of hours) that duped Göring actually led to him being hailed as a kind of folk hero during his 1947 trial (he was voted the second most popular man in Holland after the war, with citizens lobbying to raise a statue of him). Then, with impeccable timing, van Meegeren died of a heart attack two days before his one-year jail term was about to begin.

De Hory was a failed society painter (Anita Loos dumped his portrait of her in the trash, while his nude study of Zsa Zsa Gabor mysteriously vanished; the latter later declared that 'all Hungarians are liars', when informed of de Hory's crimes) whose 'more cohesive and consistent' 'Dufys' led French art experts to reject the real thing as being too tentative. He also claimed genuine Matisses to be his own fakes; 'With an ego like that, someday de Hory is liable to claim that smiling lady in the Louvre,' marvelled Life magazine. He committed suicide in 1976 to avoid extradition to France to be tried for fraud in a case brought by the long-suffering Meadows. Infamy obviously keeps prices buoyant, but interest in forgery is always reliably intense - perhaps because, as Keats says, 'Art and forgery are two sides of the same conversation.'

In fact, art forgery as we know it is a comparatively recent phenomenon, being a mere 600-or-so years old. Alexander Nagel, a Professor of Fine Arts at the New York University, has argued that forgery is a concept that barely existed in Western art before the 16th century, when the art market, along with its attendant players - dealers, collectors, connoisseurs and forgers - was born, and the focus shifted from craft to authorship. Prior to that, art served largely devotional purposes, with any attributed power residing in the object itself rather than in the hand of some omniscient maker, and a copy produces a new 'biggest art fraud of the century' (as Scotland Yard termed Myatt's case back in the '80s). Just recently, there is Tom Keating, a potbellied Cockney (he called his productions, in rhyming-slang patois, 'Sexton Blakes') and former housepainter who gave away fake Renoirs and de Hoochs to junk shops and pub acquaintances, rattled off 16 Samuel Palmers in one weekend and whose 1979 trial was dubbed 'Watercolourgate'.

Wolfgang Beltracchi, a German hippie whose facility for Max Ernsts and Heinrich Campendonks brought him patrons such as Steve Martin, as well as a property empire including a Languedoc estate and a USD7 million Freiburg villa; and Shaun Greenhalgh, who, along with his family, turned out everything from an LS Lowry painting to a Barbara Hepworth sculpture to a Gauguin statue of a faun (which ended up being acquired by the Art Institute of Chicago in 1997 for USD125,000) to Roman silver plates, all crafted in his garden shed in Bolton, a town in the north of England.

Given the current supernova heat of the art market, with fortunes to be made and magical thinking often blindsiding connoisseurs' better judgements, questions of value and authenticity assume even greater potency. 'I guess a conservative estimate might be that 30 to 40 percent of the art in circulation could be fake,' says Colette Loll. 'It's a prolific problem, and the internet has exacerbated it. I think you have a consumer mentality like the luxury-goods market, where so many people accept the really nice-looking fake Prada - what I call the 'good enough to pass' mentality. So, they'll buy something that they know, in the back of their minds, can't really be a Picasso watercolour, for, say, a thousand dollars. But it's good enough to pass. And, while the market remains so lucrative, the intent to deceive will continue.'

Back in his kitchen, John Myatt says that, of the 200 fakes he sent out, only 80 have been recovered: 'I guess the others are out there, taking on a life of their own, going into collections or catalogue raisonnés. I wonder if I'd recognise them now.' He's preparing for a show at a blue-chip London gallery, where he'll show works in his own style alongside his 'Monets' and 'Dufys'; it's important to him, he says, not to lose touch with '[his] sense of self as a painter' (and he insists that the works, such as Self-Portrait as a Flowerpot, have been well received, and the default analogy, of Björn Again or The Bootleg Beatles attempting to foist their own songs on people, doesn't quite hold water). But he knows that the 'F' word will forever be applied to him, and he's made his peace with that. 'It's my talent to ventriloquise,' he says. 'And I've got John Myatt collectors now, who are either very shrewd or very silly.' Actually, he adds, a funny thing happened a few years ago: he found out that someone was faking John Myatt fakes. 'I never got to the bottom of who was doing them,' he says, donning his smock in readiness for more Cézanne-channelling. 'It put me in a bit of a moral quandary for a moment. But, in the end, I just had to laugh it off.'