The Flair Up There: 20th Century Spaceman Style

Can you name a modern-day astronaut? It’s not a trick question. The Rake pilots a time machine to the mid 20th century – the glory days of space exploration – when the men with the right stuff became international celebrities and style icons.

Buzz Aldrin may have been the second man to walk on the moon, but he was, at least, the first astronaut to walk the New York Fashion Week runway. Two years ago, the space exploration pioneer — whose personal style is of a more bohemian bent, with gangsta levels of jewellery — moved through’s Earth gravity at a steady enough pace for an 87-year-old dressed in (what else) a metallic silver jacket from designer Nick Graham’s Life on Mars collection. And, yes, Aldrin still looked like a bit of a dude.

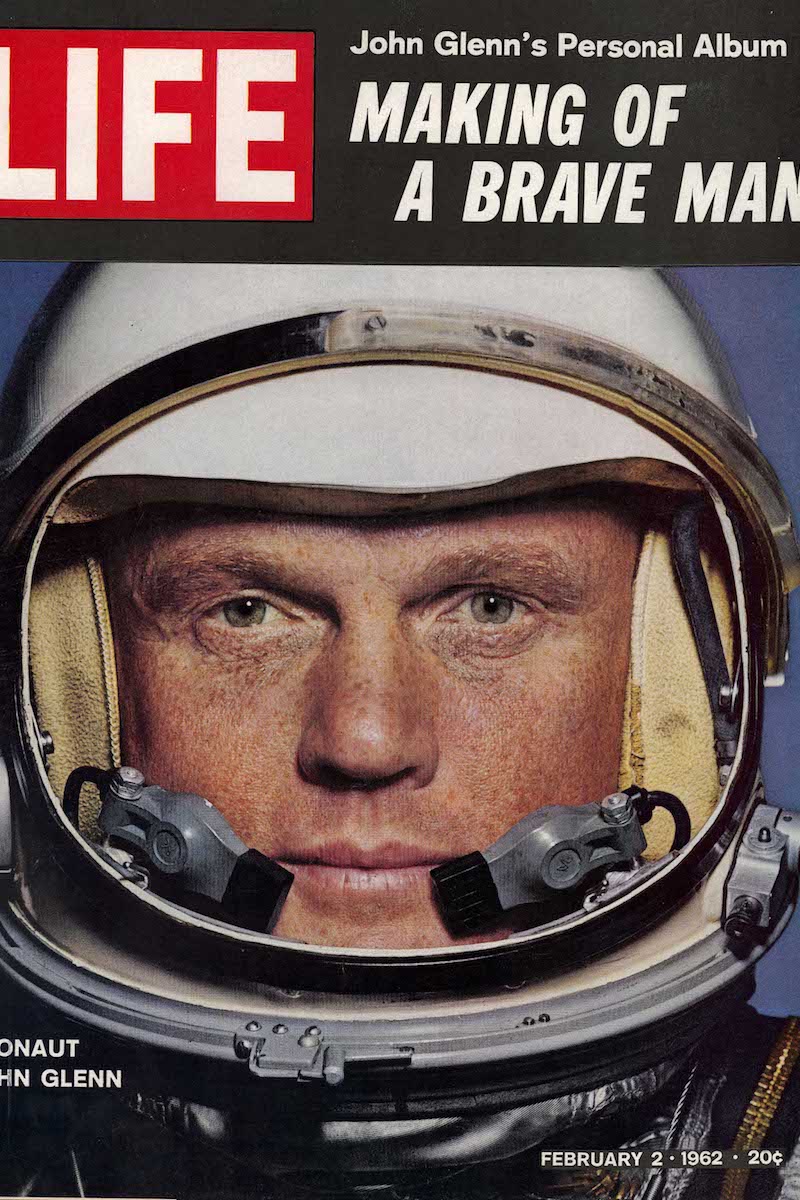

Even if we barely know the names of spacemen and women today, we know that NASA’s Mercury, Gemini and Apollo space programmes set a high bar for style, not least because they made national celebrities of the individuals chosen to fly literally out of this world — and of their families. The New York Times noted how the astronauts quickly came to embody great ‘US of A’ values, the likes of duty, faith and country: “Nobody went away from these young men scoffing at their courage and idealism,” it noted. And such was the hype that even their children became famous. Teen magazine ran an exclusive on ‘Carolyn Glenn: Astronaut John Glenn’s Daughter Reveals Why She’s Way Out in Orbit!’

Indeed, the public face of the groundbreaking, so-called ‘Mercury Seven’, in particular, was a crucial aspect of their endeavours — both as a means of selling a hugely expensive project to the public and, given that this was a symbolic race against the U.S.S.R., to rub the Russians’ noses in the U.S.’s success. At least, that was the plan — in reality, until the Americans’ moon programme, which this year marks the 50th anniversary of its first landing, it was the Russians who had most of the firsts in space. ‘Kaputnik!’ as one paper wittily dubbed another NASA launchpad failure.

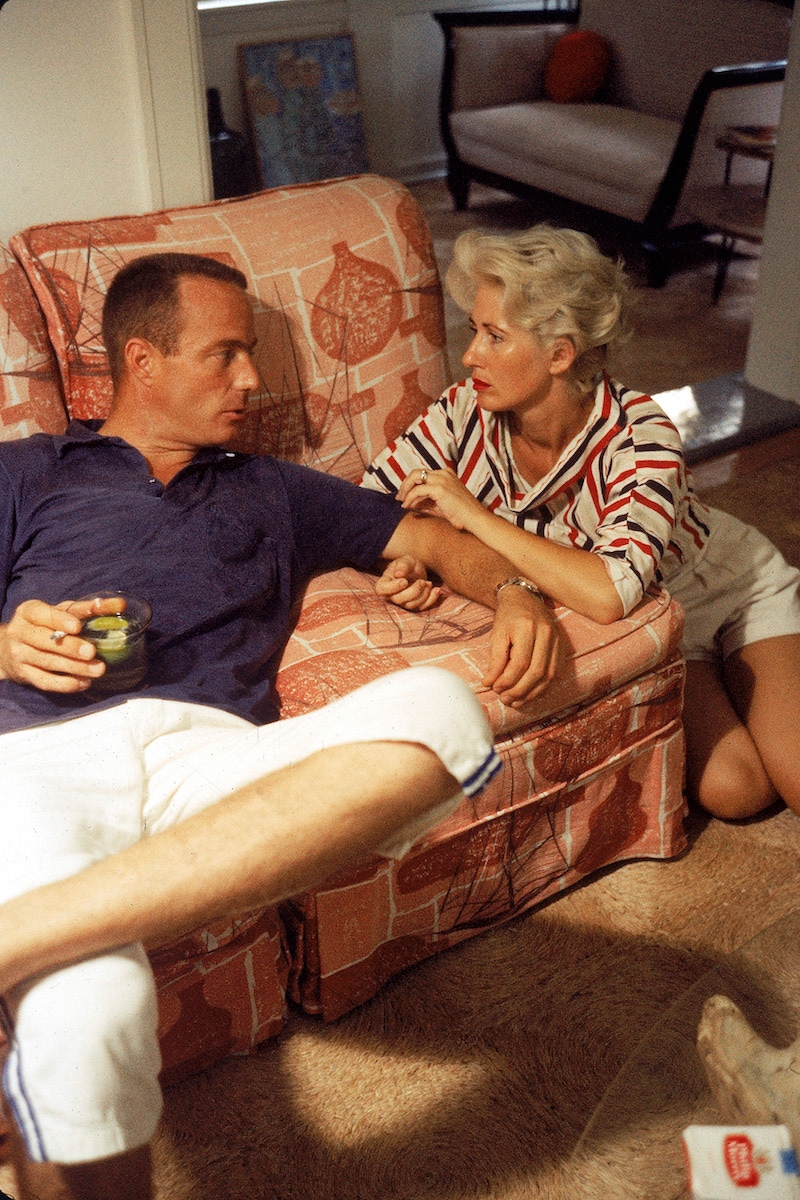

That the astronauts regularly appeared in Life magazine — which won exclusive coverage with a $500,000 deal that included the life insurance no company would grant them — underscored their status as style icons of the era and encouraged a wider interest in the lives. It was actually an idea NASA orchestrated as a means of supplementing the incomes of men who, although training to go into space, remained on the contractual pay of their military rank. Life typically pulled in sales of 10 million copies of any issue that featured the astronauts — or their wives, given rockety hairdos and space-age clothing and expected to be, as one of them put it, “perfect wives [with] perfect children [in] perfect homes”.

Photographs of these astronauts in their space-faring attire — those early Bacofoil jumpsuits, replete with zips, straps and nozzles, and the later, bulkier, all-white mobile life-support systems — are familiar to us. The less familiar images, especially with the passing of time, are of these men in their civvies, looking very much like gents of the Mad Men era, albeit ones who, as test pilots, had a high chance of dying doing what they did. As the late Tom Wolfe noted in The Right Stuff, the seminal account of the Mercury programme: “How many [men] would have gone to work, or stayed at work, on cutthroat Madison Avenue if there had been a 23 per cent chance, nearly one chance in four, of dying from it?”

There’s Gordon Cooper in a black-and-grey-striped blazer, one that can only be described as groovy. Or the rather proper John Glenn — an ultra-religious family man, a ‘my country first’ type — in his checked three-button sports jacket, white shirt and trademark bow-tie. Or Gus Grissom, with his mid-blue serge suit, white shirt and skinny burgundy tie. Then there’s the more relaxed publicity stills of them dressed for the Sunday beers and barbecues these men and their families — who were closely connected by work but also by the shadow of mortality — regularly enjoyed. There’s Deke Slayton in pale grey trousers and a polo shirt in rescue orange — akin to the shade later selected for the ‘pumpkin suit’, the launch- and entry-gear worn by astronauts on the Space Shuttle. Or Scott Carpenter in his brown mohair trousers and silk paisley print short-sleeved shirt. These men could be as sharp in dress as in wits.

Read the full article in Issue 65 of The Rake - on newstands now or available here.