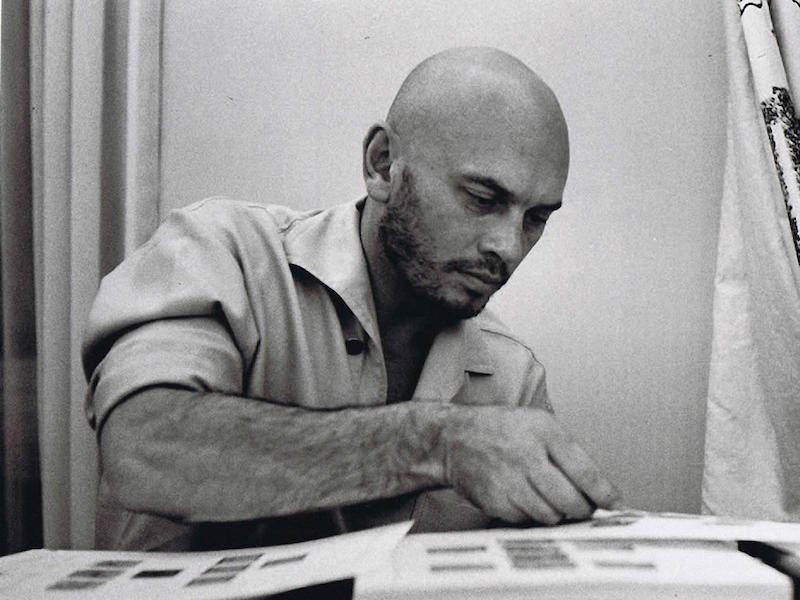

THE LOVELIEST JOKE: David Niven

In a legendary career that spanned 50 years and nearly 100 movies, David Niven had ample opportunity to become who he was: the Englishman abroad. Still, you got the impression that he couldn’t believe his luck.

One bright, balmy Hollywood morning in the mid 1930s, David Niven presented himself at Stage 29, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, for a screen test, “made up like a Piccadilly tart” and feeling ridiculous. When his turn came, he recited — “out of my panic” — an old schoolboy limerick featuring an old man of Leeds who swallowed a packet of seeds, with unfortunate foliage-bearing results for his nether regions. It wasn’t exactly a Hamlet soliloquy, but Hollywood had a vacancy for a stiff-upper-lipped Brit — the society hostess Elsa Maxwell had urged Niven westward, saying “nobody out there knows how to speak English, except Ronald Colman” — and a few weeks later, he was enrolled at Central Casting as “Anglo-Saxon Type No.2008”.

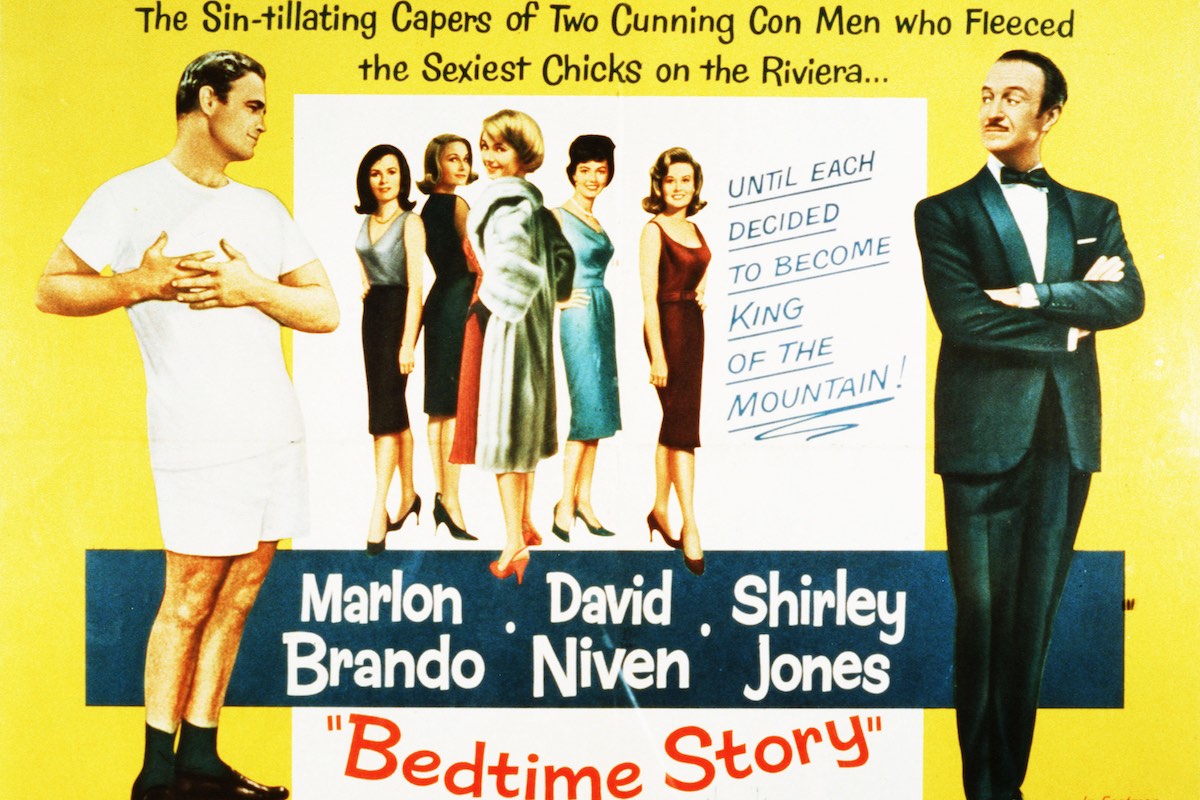

It was a billing that Niven more than lived up to over three decades in Hollywood, playing, as he put it, “officers, dukes and crooks” in such films as The Charge of the Light Brigade (1936), Wuthering Heights (1939), and 1956’s Around the World in 80 Days. His clipped vowels, pencil moustache, military bearing (he’d spent three years in the Highland Light Infantry) and slightly sardonic air made him the archetypal Englishman abroad, an outsider at the heart of the studio system, incredulous not only at his profession — “it’s just playing children’s games in front of the grown-ups,” he remarked in a 1972 interview — but also at counting the likes of Errol Flynn and Humphrey Bogart among his best friends. When he won the best actor Oscar for Separate Tables in 1958, he announced, on reaching the podium, that he was “loaded with lucky charms”, though any casual onlooker of his career would have noted the very British mix of chutzpah and winging it that, with the requisite dollop of good fortune, had got him there.

Niven was born in Belgravia in 1910; his father, an army reserve lieutenant of Scottish descent, was to die five years later at Gallipoli. “I had not seen him much except when I was brought down to be shown off before arriving dinner guests or departing fox hunting companions,” Niven later wrote in his bestselling memoir The Moon’s a Balloon. His mother, of French descent, was “very beautiful, very musical, very sad, and lived on cloud nine”. Widowed and cash-strapped, she married the Tory MP Sir Thomas Comyn-Platt, who rattled his cufflinks at Niven “when I made an eating error at mealtime”, thus inaugurating his lifelong habit of cock-snooking at authority figures, be they chilly stepfathers, sadistic sergeant-majors or boorish studio heads.

Young Niven bounced from school to school, a “self-appointed jester to the upper classes”. Provided with a “grubby little garret” at the heart of St. James, he lost his virginity at 14 to a prostitute called Nessie, who had ‘rooms’ in Cork Street. (She helpfully provided him with a book of pornographic photos before taking him in hand.) He eventually washed up at Sandhurst. “It was never pleasant to be treated like mud,” he wrote, “but Sandhurst, at least, did it with style.” His subsequent three years in the Highland Light Infantry were spent mostly on Malta. He rose to lieutenant, but had little to do but burnish his handicap at the Marsa Polo Club, which he described as “mounted suburbia”. By now, there were major diversions: a friendship with the actress Anne Todd had led to his becoming “incurably stage-struck”, and he’d also discovered girls: “I had a heart like a hotel, with every room booked.” His frustration with the army boiled over when he insulted a visiting major-general, and he resigned his commission, rather than face a court-martial, in 1932.

Read the full story in Issue 69 of The Rake - on newsstands now. Subscribe here