The Trenchcoat: An Alternative Perspective

What do you think of the trenchcoat? What visions of grandeur might its long and lofty history bring forth in your mind? Depictions of the ennobled British army officer perhaps, soldering on with his stiff up lip firmly in place or perhaps returning home from the front, world-wearied and jaded, or else the chastened film noir heartthrob wandering the streets with his fedora a-drenched in the pouring rain.

Of course, these rather romantic visions of trenchcoat clad heroes have their place – it’s no great secret that the trenchcoat’s origins are in the rubberised ‘mackintosh’ riding coats of the nineteenth century and that in the twentieth century, the trenchcoat was invented to buffer the British military against the demoralizing mire of the trenches during the Great War – and has remained a reliable, supportive garment to have in the wardrobe ever since. For this reason, it’s retained a rather aristocratic, elevated image as the serious overcoat of high society doyennes and high-flying Hollywood living, but what of the other less auspicious elements of the trenchcoat’s storied history – the side that’s seldom talked about?

It may well be the glamorous coat of the polished military man or strong-jawed Hollywood anti-hero, but it’s also earned a rather risqué name for itself as the undisputed coat of flashers and philanderers. The trenchcoat of course, is the perfect vehicle for the job; easily repurposed with its tall collar, generous double-breasted wrap, belt for extra security where required and even better, its two slit-through side pockets which allow for one to reach beneath the coat to whatever lurks beneath. Small wonder then that it should come to be the coat of choice for those who feel the irrepressible need to bare all in front of a crowd; whether that be a jubilant celebration of your team’s success on the sporting field, or else to frighten eligible young ladies half to death on the Subway.

But how should such an outré tradition come about? Put simply, as Hollywood pumped out its impossibly glamorous silver screen framed dreams across the Western World throughout the forties and fifties, the trenchcoat became the coat of choice for lovable rogues and disreputables, men of the world and irrepressible femme fatales. For example, in 1941’s The Maltese Falcon, Humphrey Bogart wore the quintessential beige double-breasted Aquascutum trench, before wearing it again in Casablanca in 1942 as he bid Ingrid Bergman goodbye with steely detachment, and again in 1946 as private eye Philip Marlowe in The Big Sleep. Audrey Hepburn famously dressed in a short tan trench for the closing scene of Breakfast at Tiffany’s in 1961 and in 1971, the brooding, embattled figure that Michael Caine cut in Get Carter, in his black double-breasted trenchcoat has led to the coat becoming as synonymous with the modern British gangster as it has with the film itself. Alain Delon, who wore his in the 1967 crime thriller, Le Samouraï wore his coat with similarly stoic élan, positively smouldering his way through an impossibly stylish narrative.

It also, curiously, has become synonymous with the cinematic sleuth, presumably because it also channels a subtle sense of mystery and quite literally lends itself to concealment. The iconic (although admittedly not altogether rakish) image of Inspector Clouseau’s beady eyes poking out between hat brim and turned-up collar, more or less sets the tone. There are nonetheless, cooler associations between the trenchcoat and the super-sleuth; another of Michael Caine’s iconic roles from the sixties, secret serviceman Harry Palmer in The Ipcress File, has Caine sporting a simple single-breasted mac. In Blade Runner, both the Replicant Roy Batty, played by Rutger Hauer and Harrison Ford’s Rick Decard wore voluminous, futuristic trenchcoats (Hauer in a terrifying dark leather number and Ford in a tan treated cotton single-breasted design) and likewise The Matrix trilogy abounds with long, leathery, stature-raising trenchcoats as worn by the legendary Lawrence Fishburn as Morpheus or Keanu Reeves’s Neo.

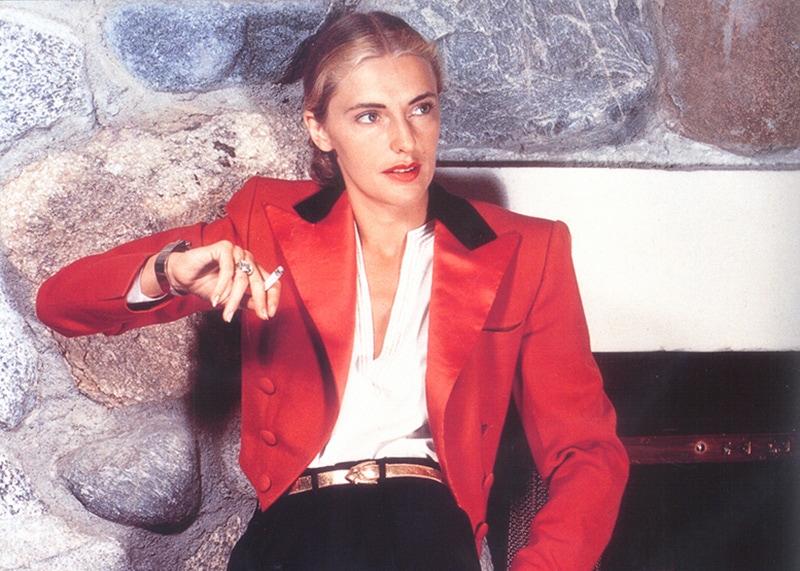

This association with secrecy, and the coat’s ability both to blend into a crowd and hide a great deal in doing so, has also occasionally led a fair hearted maiden to do just that, using the coat’s powers of concealment to invoke a serious amount of sex appeal; whether that be surprising a loved one with nought but lingerie beneath her coat as he returns home from a trip abroad, or else playing dress up in order to spice things up in the bedroom. Such risqué surprises are genuinely sexy, but there’s a great deal of difference between a scantily clad secret which remains between a young couple and a middle aged man revealing his old chap on the top deck of a bus.

In reality, nice though it might be think otherwise, wrapping a trenchcoat around your shivering gentleman-sausage and sneaking about like some sort of nude assassin is not going to do your street cred a huge favour. In truth, this enduring association with the smouldering mystique of Hollywood’s greatest hits has evidently filtered into the realm of delusion. It seems that men and women, who invariably don’t look like Hollywood style icons have, over the years, repeatedly seen fit to don and then un-don the trenchcoat to channel an air of (albeit misguided) virility and excitement. This rather entertaining assertion nonetheless belies a simple truth – although stripping beneath a trench is seldom advisable, they have nonetheless endured as a symbol of sex appeal and suavity. Indeed, so potent is the trenchcoat’s power as an aphrodisiac that it evidently compels a good portion of the populace to get naked underneath. Which is why when all’s said and done, you could do a lot worse than invest in a new trenchcoat this spring – it’ll increase your attractiveness ten fold – but for god sake, don’t feel the need to bare all beneath it once you have. After all, as Mark Twain once said, “clothes make the man. Naked people have little or no influence upon society.”