FOR ONE BRIEF SHINING MOMENT

What might have been? What might have been had John F. Kennedy avoided Dallas in November ’63? Would he have remade the world? For as long as we yearn for the counterfactual, the legend of Camelot endures..

Not long ago, I was in Dallas on business. I made the requisite pilgrimage to Dealey Plaza and viewed the world’s most infamous grassy knoll, but I also discovered one of the more striking monuments among the thousands to John F. Kennedy. The Sixth Floor Museum is housed in the building that was once the Texas School Book Depository. You climb the stairs, turn a corner, and are faced with the open window through which Lee Harvey Oswald fired his rifle at Kennedy’s motorcade on the afternoon of November 22, 1963, with world-shattering consequences. The museum plays host to around 400,000 people a year, and their comments in the visitors’ book — “Our greatest President”; “Oh how we miss him!”; “A beacon of hope, cruelly extinguished” — are ample evidence that, more than half a century on, the Kennedy mystique has only deepened and intensified.

On paper there seems scant reason for this enduring hagiography. After all, Kennedy spent less than three years in the White House. His first year was a disaster, by anyone’s standards. The Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba collapsed in farce; he was humiliated by the pugnacious Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev at their 1961 summit; and most of his legislative proposals were nixed by a hostile Congress.

But the Kennedy myth has less to do with the quotidian business of getting bills passed and more to do with the way he came to embody those ideals — purpose, hope, vigour, strength, drive — that America has always held dear. In this, history was on his side. He was the youngest man ever elected to the presidency, at the age of 43, succeeding Dwight D. Eisenhower, then the eldest at 71. He was the first president born in the 20th century and the first veteran of world war II (in which he’d commanded a PT boat) to win the White House, thus symbolising a new generation and its coming-of-age. And, not incidentally, he projected an image of youthful elan that was perfectly timed for the nascent televisual age. Anyone who studies the grainy footage of him in full declamatory meet-and-greet mode is sure to be struck by his charismatic presence and the ringing elegance of his oratory. His celebrated inaugural address was stuffed with phrases that seemed formulated to be carved in stone, as many of them subsequently were. For one of the most famous, he simply lifted a motto from his prep-school days, substituting “your country” in place of “Choate”: thus, “Ask not what your country can do for you — ask what you can do for your country”. A command that propelled legions of Americans into teaching, government service, or the Peace Corps and its ilk, was coined.

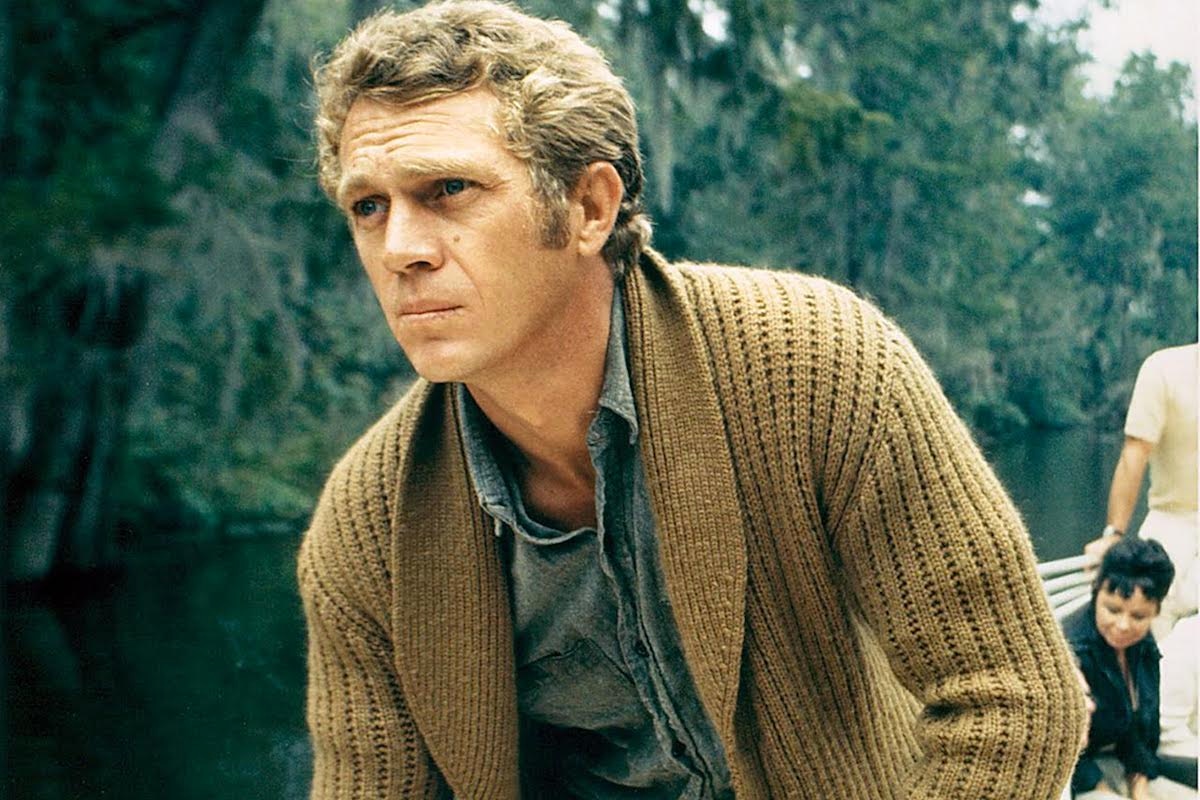

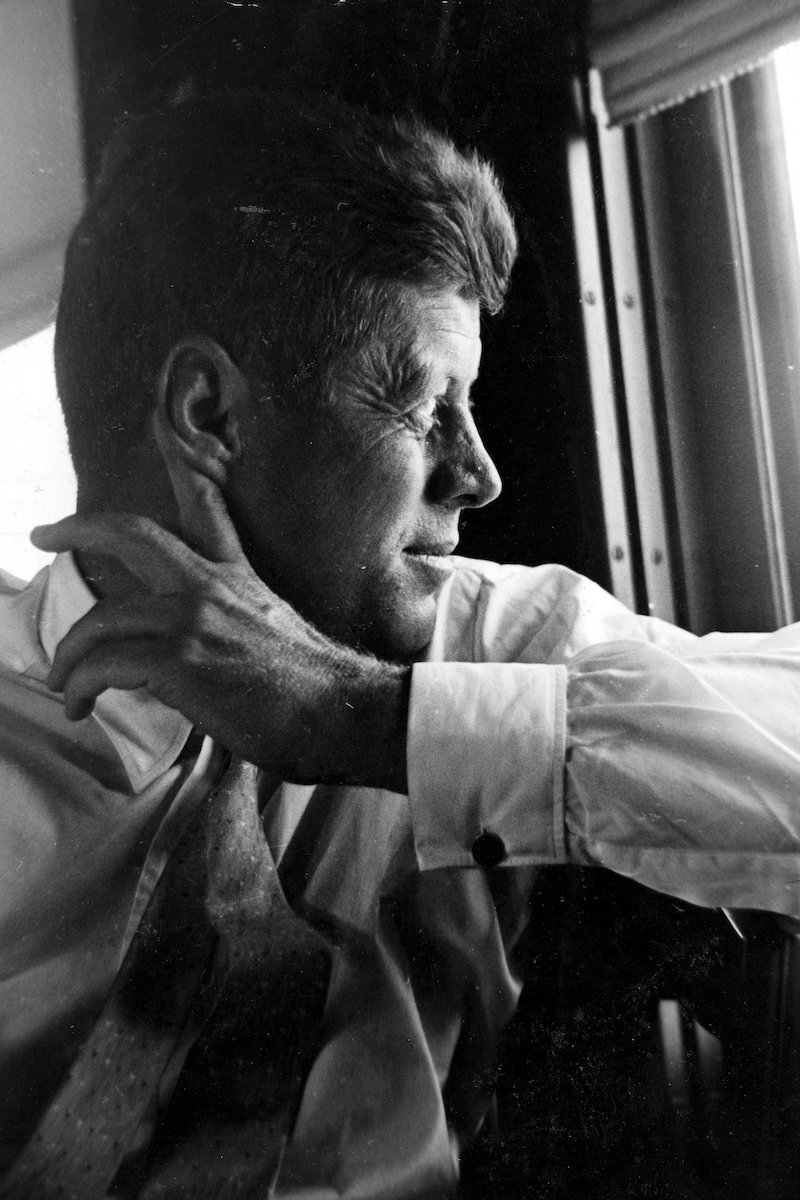

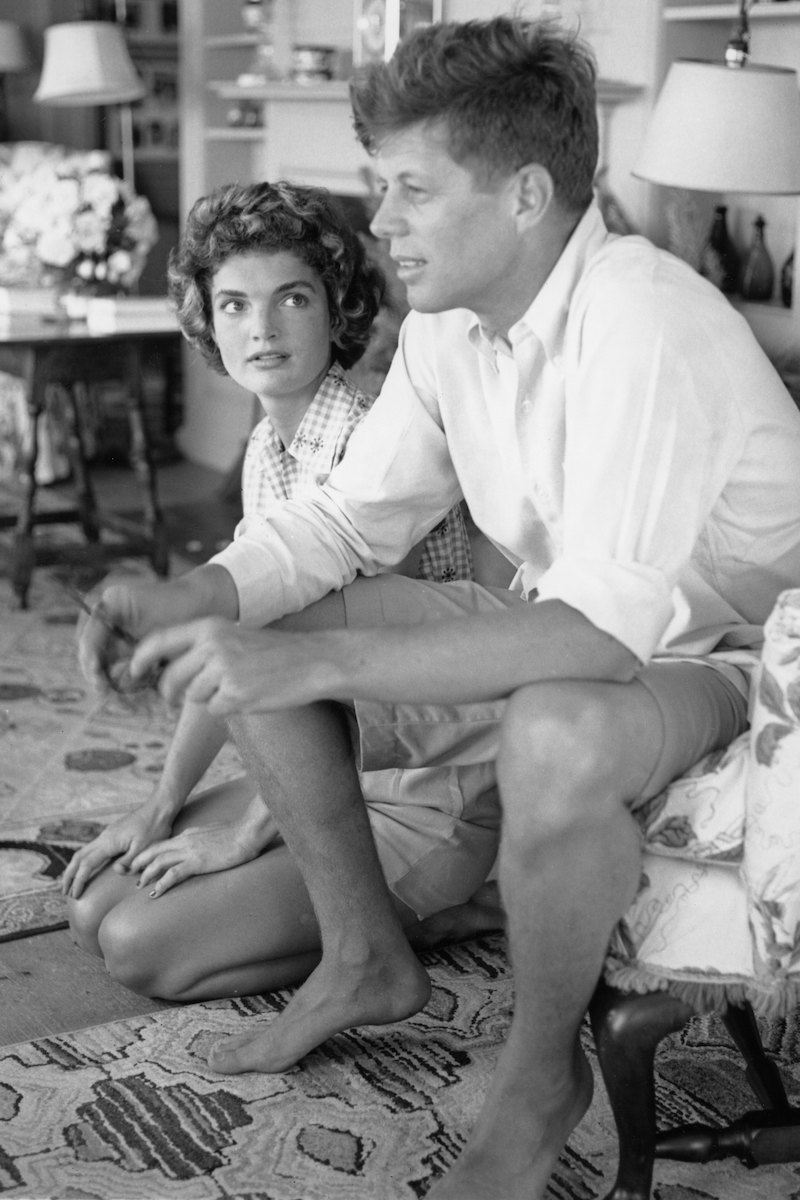

All this served to burnish the J.F.K. brand, along with something more ineffable, and which a friend of his, the journalist Ben Bradlee, defined in the title of his 1964 book about Kennedy as That Special Grace. It was there in his pragmatic good looks and athletic mien; it was there in his equally charismatic wife and children. Think of those Slim Aarons-esque images of the president, in Wayfarers and windbreaker, sailing in his yacht, the Honey Fitz, off Hyannis Port, or the informal shots of him playing with his children in the Oval Office, or with his daughter Caroline seated on his lap aboard Air Force One. Think, also, of the crisp, modern lines of his presidential attire. “He was careful to give that unstudied sense of ease in his dress that he cultivated in his press conferences,” wrote the author and menswear historian G. Bruce Boyer, “a nice balance of seriousness and lightness, profundity and humour, calculated intuitiveness.” Kennedy adopted what Boyer calls “a modified Ivy League style, an Eastern Establishment business look”, with “two-button, pinstriped and dark grey worsted suits, cut in a modified Ivy style with small, soft shoulders, shallow chest, and little waist suppression — perfect in their simplicity”. Off-duty, “polo shirts, and boating shoes without socks, became a weekend uniform”. And to hone his man-of-the-moment aesthetic further, Kennedy was the first president to go largely hatless. Long before Ronald Reagan, J.F.K. became the first movie star to occupy the White House, inspiring reverence among his inner circle. The journalist and historian Theodore White, one of that circle, wrote in his memoirs: “I still have difficulty seeing John F. Kennedy clear. The image of him that comes back to me… is so clean and graceful — almost as if I can still see him skip up the steps of his airplane in that half lope, and then turn, flinging out his arm in farewell to the crowd, before disappearing inside. It was a balletic movement.”

The Kennedys also took pains to ensure that their White House was outward looking and plugged into the wider culture; among the writers, artists and intellectuals that received invitations to Pennsylvania Avenue were the cellist Pablo Casals, the poet Robert Frost, and the French intellectual André Malraux. Kennedy had graduated from Harvard, and peppered his administration with that august institution’s professors. Poets and philosophers were also amply quoted in his public speeches. This vision of J.F.K.’s tenure as a sort of best-and-brightest apogee was burnished after his assassination, not least by Jackie Kennedy. In a famous interview with Theodore White for Life magazine, she reminisced: “At night, before we’d go to sleep, Jack liked to play some records; and the song he loved most came at the very end of this record. The lines he loved to hear were, ‘Don’t let it be forgot, that once there was a spot, for one brief shining moment that was known as Camelot’.” The song came from the Broadway musical Camelot, and the lyrics were by Alan Jay Lerner, who just happened to be J.F.K.’s classmate at Harvard, but Jackie’s nudge did the trick: the equation of the Kennedy years with a semi-mystic Arthurian romantic ideal has persisted ever since.

There’s never been any shortage of people willing to dull the Kennedy halo. Scholars concur that he was a good president but not a great one; a poll of historians in 1982 ranked him 13th out of the 36 presidents included in the survey. There are the allegations of vote rigging in the 1960 election, enabling Kennedy’s father, Joseph, one of the wealthiest and most ruthless men in America, to effectively buy his son the presidency; there’s the supposed Mafia connections; and, of course, there’s the Olympian philandering that posed such knotty logistical challenges to Kennedy’s secret service detail. The image of youth and vitality is itself a myth; Kennedy wore a back brace and spent much of his life in hospitals, battling a variety of ills. Gore Vidal, who was related to Jackie Kennedy by marriage and had a ringside seat during Kennedy’s imperial phase, was an agnostic from the start. “Kennedy looks older than his photographs,” he wrote in a piece for The Times in 1961. “The outline is slender and youthful, but the face is heavily lined… his eyes are very odd. They are, I think, a murky, opaque blue, ‘interested’, as Gertrude Stein once said of Hemingway’s eyes, ‘not interesting’; they give an impression of flatness… his stubby boy fingers tend to drum nervously on tables… he is immaculately dressed, although occasional white chest hairs curl over his collar.” Nigel Hamilton, author of JFK: Reckless Youth, went further. “Once the voters or the women were won,” he wrote, “there was a certain vacuousness on Jack’s part, a failure to turn conquest into anything very meaningful or profound.”

And yet. Kennedy’s perennial allure rests as much on his willingness to carpe diem as it does on any carefully crafted image management. He followed eight years of Republican stagnation and presented himself as a dynamic corrective. “I have premised my campaign on the single assumption that the American people are uneasy at the present drift in our national course… and that they have the will and the strength to start the United States moving again,” he declared in 1961. And he gave impetus to the idea of pursuing a national purpose, with his adept stewardship of the Cuban missile crisis in 1962, his launching of a drive for a civil rights bill, and his enthusiastic backing for NASA’s space programme (“We choose to go to the moon in this decade… because that goal will serve to organise and measure the best of our energies and skills”).

For all his contemporary impact, however, the reason the Kennedy legend remains so potent is the might-have-been factor. Had he lived, would he have transformed the nation and the world? His own prime has been conflated with that of the nation’s; he reminds many Americans — and others — of an age when it was possible to believe that politics could address society’s moral strivings and be harnessed to its highest aspirations. The window of Dallas’s Sixth Floor Museum now looks out on a harsher, more insular and more bellicose political landscape; with shining moments, brief or otherwise, being pretty thin on the ground, Kennedy’s Camelot has come to rank alongside the mist-shrouded original as a lost, and perhaps all but unrecoverable, idyll.

This article originally appeared in Issue 60 of The Rake.