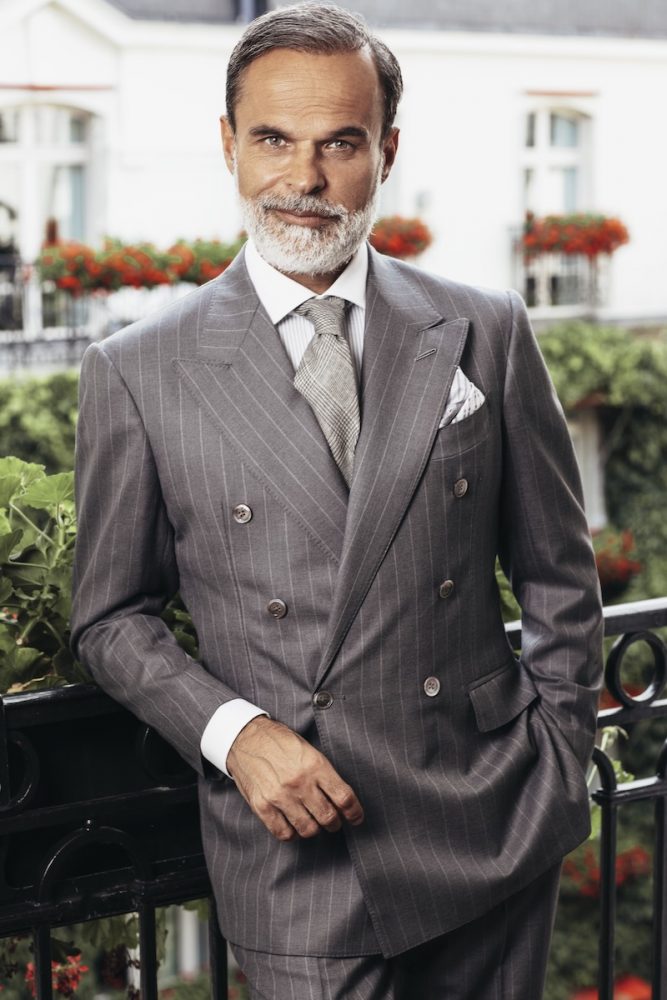

The characteristics of the Double-Breasted Jacket

The double-breasted jacket has fallen in and out of favour over the last century, yet today its position amongst the menswear greats is permanently cemented. The Rake explores…

The double-breasted suit spent a good while in the wilderness. We vividly recall American GQ making a big thing of it when, in 2011, they featured a DB on the cover for the first time in 13 years. “The double-breasted jacket has come back in a big way this year,” they crowed, encouraging readers brave enough to adopt double-breasted suiting, “if you see a fellow DB’er in the street, shake his hand. After all, you’re part of a movement.” No longer such a bold sartorial statement (nor indeed, the mark of belonging to a ‘movement’), the DB is now utterly mainstream — as it has been at regular intervals over the past century-plus.

Origins

The style has its origins, as with so many menswear staples, in the military. In the late 19th century, gentlemen took to wearing coats stylistically similar to naval reefer jackets during more casual moments (at leisure in the country or en route to the tennis court, perhaps), but the garment was initially considered far too informal for the office or other dressy settings. This changed, in no small part due to the DB’s championing by the Prince of Wales (later, the Duke of Windsor), in the 1920s and ’30s. Leading British tailor Timothy Everest says, “The Golden Era for the double-breasted suit was the ’30s, between the two World Wars, where everyone lived a bit larger than life. At the time, the heightened elegance of the double-breasted suit fitted perfectly.”

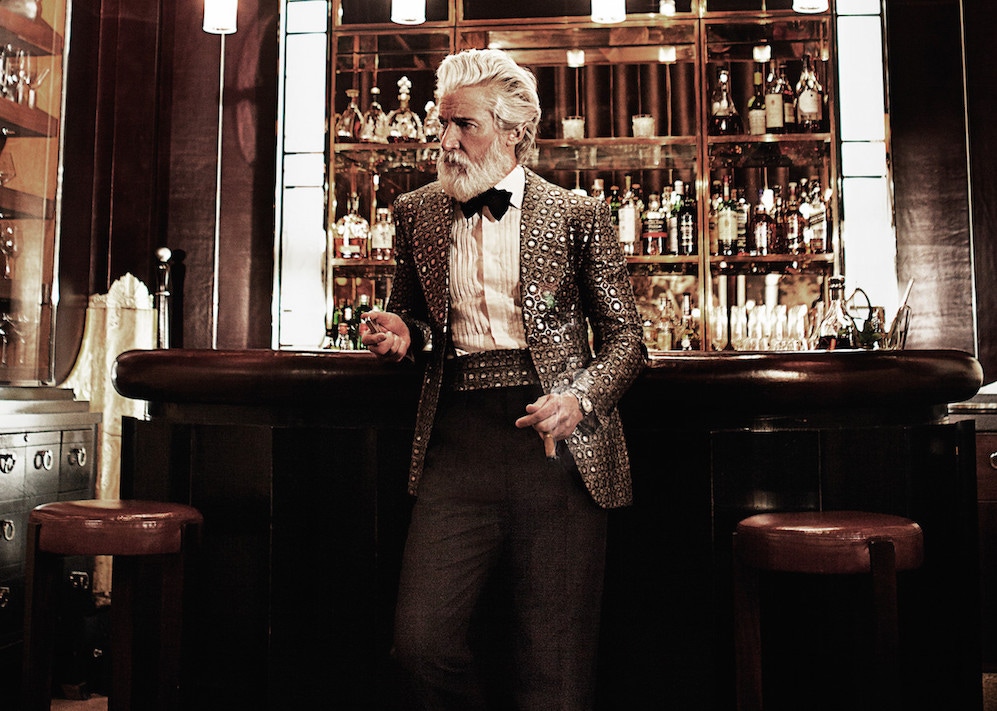

With the Second World War, the double-breasted suit became a rare bird indeed, as textile shortages led the British government to proscribe such profligate use of cloth. A notable wartime appearance of the DB came in the classic 1942 film, Casablanca, where Humphrey Bogart's Rick Blaine sports a beautiful ivory shawl-lapel dinner jacket. Like fellow vertically-challenged DB proponents Fred Astaire and the Duke of Windsor, Bogart time and again disproved the common belief that a double-breasted jacket is ill-suited to the shorter gentleman. For the lilliputian fella, successfully rocking a DB is merely a matter of carefully playing with coat length (keep it short to create the illusion of height), button-stance (more on that below) and proportion.

Who Wore it Well?

In the post-war period, the DB enjoyed a gradual return to favour (particularly with Hollywood stars of the 1950s), before disappearing once again in the 1960s, when slimline single-breasted tailoring à la Mad Men ruled the roost. In the broad’n’bold seventies, the DB made a comeback courtesy of iconoclastic tailoring house Nutters of Savile Row and a young American designer named Ralph Lauren, who wore his obsession with classic cinematic style on his monogrammed sleeve. Giorgio Armani and Hugo Boss made 6x1, 4x1 and 2x1 button-stance double-breasted suits the signature look of the 1980s (as seen on TV, worn by the likes of Miami Vice’s Ricardo Tubbs and Pierce Brosnan’s Remington Steele). With ubiquity, a backlash inevitably ensued, and when Hedi Slimane’s razor-thin fit came through at the turn of the century, the ‘bulky’ DB was relegated to desperately dated status.

Now, the swings and roundabouts of stylistic whimsy have turned in its favour. “After what seems an eternity of skinny lapels gracing skimpy suits, we are thankfully seeing a return to a more classic proportion in tailoring,” says menswear expert Christopher Modoo. “With the appetite for pleated trousers, longer coats and wider lapels comes a renewed interest in the double-breasted. The longer, wider lapel is supremely elegant, and we have a generation of young sartorialists who do not have the negative associations of the 1980s and early ’90s, and instead think back to the golden age of Hollywood and the 1930s.”

The Double-Breasted Jacket Today

It’s unsurprising that the DB is back, in this period when individuality has become more important than ever to consumers. The double-breasted jacket is immensely customisable, and much of this quality comes down to the buttons that are a DB’s central focus. Unlike the single-breasted jacket, where the line remains very similar across one, two and three-button configurations (due to the fact that generally, and correctly, only one button is fastened), there’s an array of unique button-stance and deployment choices available to the DB wearer. The last word on button-stance — and how it might be used to most flattering effect — goes to menswear and horology commentator Peter Chong, writing in The Rake in 2009: “The most common button configurations of the DB are the 6x2 and 6x1… A 6x2 shows six buttons, of which the bottom right two may be buttoned, and the topmost two are for display only; in the 6x1, a long lapel sweeps past the top four buttons to close on the last one. A 4x1 configuration is also popular and features the same long lapel. As the sweep of the lapel ends at the buttoning point, the placement of these buttons are of great importance. The buttoning point provides the anchor for the coat and the lower skirt pivot.” Bespeaking a DB jacket, Chong advises: “For a 6x2, start with the lower four buttons arranged in a square, about 4.25 inches apart. If you are athletic-looking — tall and well built — this will be the best balance. For those who are a bit wider at the waist, shifting the bottom two buttons down slightly (no more than 1 inch) will elongate this square, and create the illusion of height. For those who are very slim, widening the stance of the buttons will provide the illusion of width. Don’t overdo this aspect — move the buttons no more than 1.5 inches further than they were originally set, so as not to upset the balance. “The upper two of the lower four buttons (on a 6x2) should anchor the coat, just above the natural waist. The Duke of Windsor, however, had the habit of only buttoning the lower button of his 4x2s and 6x2s, in what is known as the ‘Kent’ style, named after the Duke of Kent, who’s credited with starting the trend. The 6x1, because of the lower buttoning point, emphasises the length of the lapel, and is particularly useful for the more diminutive gentleman. The Duke of Windsor, Fred Astaire and Ralph Lauren have all used this style to their advantage.” The 6x1 is especially popular with Parisian tailoring house Cifonelli, and Christopher Modoo, who says, “My favourite version is the lower buttoning style. It has a long, leafy lapel that gives height to the wearer. It can be sporty when paired with side open patch pockets or formal when faced with silk lapels and closed vents. Critically, it can be worn open. Contrary to received wisdom, a low buttoning style looks suitably rakish left undone, especially with a waistcoat underneath. The look, when well executed, reminds me of the evening tailcoat.”