George ‘‘Beau’’ Brummell: The Originator of Dandyism

Often misinterpreted as a ‘fop’, Beau Brummell was in fact an innovative dresser and arbiter of good taste who laid the foundations for tailoring as we know it today.

“How about a pair of pink sidewinders and a bright orange pair of pants? You could really be a Beau Brummell baby, if you just give it half a chance.”

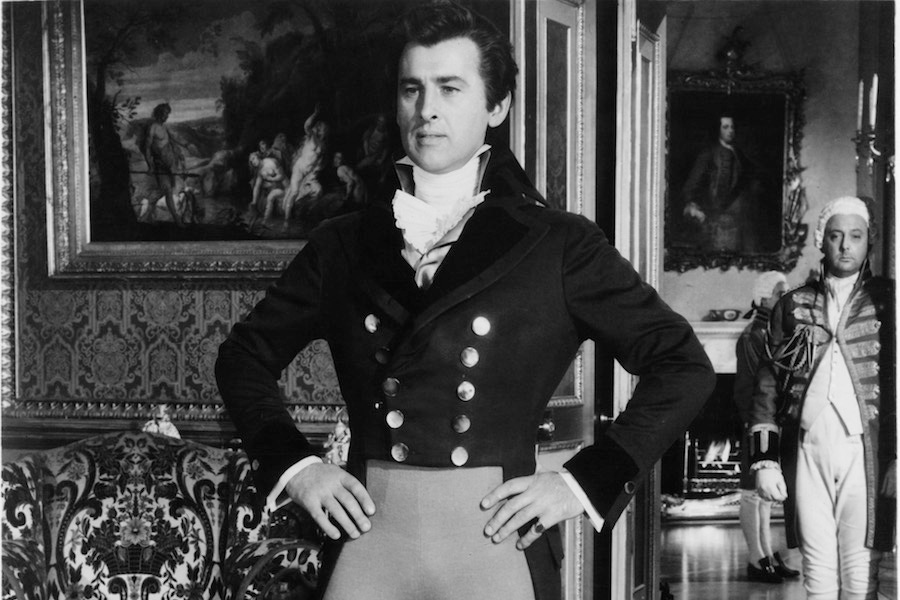

… So sang Billy Joel in his 1980 protest song ‘It’s Still Rock and Roll to Me’. Whilst Mr Joel makes some insightful and honest lyrical observations relating to fashion and the current music scene, he also makes the classic mistake of confusing the dandy with the fop. Had George "Beau" Brummell been alive in the late 20th century, I doubt he would have worn bright orange trousers or sidewinders in pink - whatever they may be. Born in 1778, Brummell is celebrated as the originator of dandyism. A very British reaction to the excessive continental fashions that dominated early Georgian London. It was here that young affluent males adopted flamboyant ‘Macaroni’ fashions picked up from visiting Italy and France as part of The Grand Tour - a coming-of-age trip undertaken by British nobility and the landed gentry from the 17th century onwards. They’d wear high, powdered wigs, make-up, perfume, elaborate and rare fabrics and silk stockings. They were the fops. Brummell advocated and championed good tailoring, sombre fabrics, a limited colour palette, personal hygiene, starch and polish. He was to Regency London what we would now call an ‘influencer’, albeit with more class. Through his time in the Tenth Royal Hussars he became good friends with the Prince Regent, the future George III, who was an admirer of Brummell’s aesthetic, quick wit and charm. With this royal patronage, Brummell became a leader of fashion and the antithesis of the fop. There is a great scene in the television drama Beau Brummell: This Charming Man where Brummell, played by James Purefoy, is confronted by a couple of fops in the street. ‘Fop’ and ‘dandy’ are hurled as insults before a scuffle breaks out and the fops are beaten up by Brummell with the assistance of his valet. There is a slight tongue-in-cheek Quadrophenia feel to the episode, with the fops and the dandies taking the place of the mods and rockers. Phil Davis, who played Brummell’s valet, also starred in Quadrophenia. Coincidence? I think not.

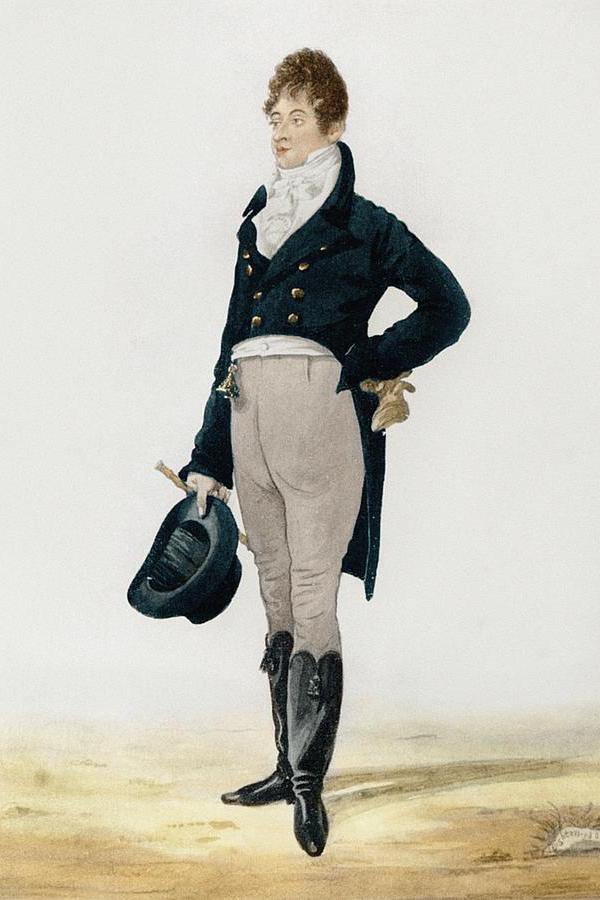

The well-fitting coat was key to dandyism. Executed in dark blue wool, it was down to the tailor’s skill to create the perfect silhouette with numerous fittings. Brummell was reputed to sit in the window of his London club casually criticising the tailoring of his contemporaries in the streets of St James’s. The pattern of the coat was equestrian in nature and is a close relative of the contemporary Savile Row dress coat still worn for white tie occasions. This was worn with full-length trousers rather than knee-length breeches and I think we can all thank Beau for this development. Although he is often cited as the inventor of the modern suit, it is interesting to note that the trousers he wore were made in a complementary fabric rather than the same cloth. The matching suit did not become fashionable until much later in the 19th century, before dominating the 20th century. With the dark plain coat, an off-white shirt and a linen cravat was worn. The concept of a dark suit and lighter shirt is a practice still recognisable today in international business dress - it is both respectful and practical. The shirt and cravat required regular laundering and starching, and Brummell advocated country washing to keep them fresh. Even today, London-based contemporary dandies send their collars to the south west of England where the soft water affords better results to the starching process (or is that just me?).

Tying the perfect knot in your cravat was a skill and Brummell would discard his failures that were imperfect or, indeed, too perfect. With the benefit of modern technology, Brummell could have made an instructional video for YouTube or a live video on Instagram. The Regency equivalent was to allow gentlemen to watch you prepare for the day live from your dressing room. It is reputed that Brummell could take up to five hours whilst attending to his ‘toilet’, so I hope the events were catered.

The perfectly polished shoe is still a good sign of character and Brummell famously requested that his boots should be polished with Champagne. I have heard that some devoted polishers use this method to create the desired patina. But to put this into context, we should remember that Brummell was a contemporary of The Napoleonic war and to use France’s finest export for cleaning boots was perhaps a personal gesture of patriotism.

Ultimately, Brummell died in poverty after fleeing London unable to settle a gambling debt. He also lost favour with the monarch after making a flippant comment about his girth. But just like Billy Joel’s ‘It’s still rock and roll to me’, he couldn't resist just telling it like it is.